THE COST OF RACING: FORMULA FORD

For more than 50 years, Formula Ford has been the development category of choice for many racers straight out of karting. As Heath McAlpine discovered, most of the country’s top professional drivers learned their craft in Formula Ford.

Cost of Racing – Formula Ford

It’s amazing to think how many of this country’s – let alone the world’s – top drivers have come out of Formula Ford.

A majority of the drivers on today’s Supercars grid, a few the current crop of Formula 1 drivers, and many more front runners got their very first taste of car racing in the Ford-powered open-wheel class.

Established as a transition category from karting and as a training ground to teach drivers the art of car control and racecraft, the tightly controlled category was born in the UK in 1967.

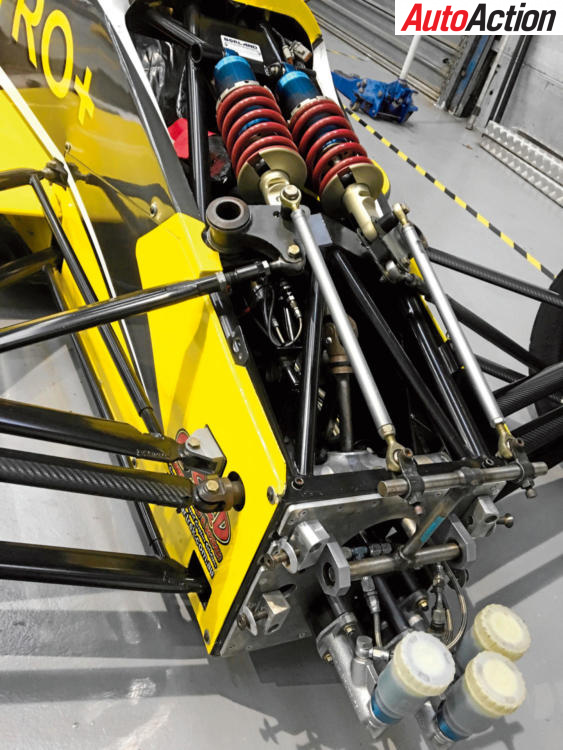

The premise was simple … a rear-engined spaceframe chassis powered by a 1600cc Ford engine from the Cortina, wrapped in a flimsy fibreglass body with no aerodynamic embellishments.

With little change, Formula Ford continues to exist in that form around the world today.

Australia saw its first demonstration race in 1969, and the first series raced in 1970, won by Richard Knight in a locally built Elfin. Legendary Larry Perkins won it in the same car in 1971 and since then, the rollcall of winners includes just about every big name in the sport here.

Jamie Whincup, Craig Lowndes, David Reynolds, Will Davison, Garth Tander, Russell Ingall and Mark Larkham are among the earlier era champions, and since 2009 there was a run of young gun titlists … Nick Percat, Chaz Mostert, Cam Waters, Jack Le Brocq and Anton De Pasquale.

Formula Ford lost its national championship status in 2013 with the controversial introduction of Formula 4, which ironically it has now outlived.

And it is also no longer a consistent support series to the Supercars Championship, having found a balance to its schedule between predominantly state-based events with the odd national-level meeting thrown in.

In a bid to reduce costs and make the category more relevant to its contemporary road car range, Ford Australia introduced its 1.6 litre Duratec engine to Formula Ford to replace the almost historic Kent engine in 2006.

The Duratec was the only eligible engine for several seasons, until the category took a step back from championship to series status in 2014, allowing the use of the Kent engine in a sub-class.

It is also no longer a consistent support series to the Supercars Championship, having found a balance to its schedule between predominantly state-based events with the odd national-level meeting thrown in. Cost-cutting has been a major factor in the recent resurgence of the Formula Ford category, which up until a couple of years ago awarded a trip to America to contest the Road to Indy Shootout to the series winner.

Accessibility for competitors has grown due to not only the choices made by the Formula Ford Association in terms of its calendar, but also through technical regulations which put an emphasis on keeping costs down.

This has helped open the class up to genuine father and son teams, who prepare their entry together.

Alternatively, some competitors prefer driving for a professional Formula Ford team.

Borland Racing Developments, headed by Mike Borland the creator of the Spectrum chassis, Mick Ritter’s Sonic Motor Racing Services which utilises the French

Mygale chassis, BF Racing led by Brett Francis, or Justin Cotter with Synergy Motorsport are among the professional alternatives.

That does not mean that father-son teams have no chance against the big teams, in fact last year’s runner up Zac Soutar was an example of a family-orientated squad pushing a big operation such as Sonic.

Carrera Cup racer Cameron Hill is another example of this when he won the series in 2015, while Cody Burcher and Cody Donald are two further father-son operations, and among the favourites for this year’s title before it was cancelled recently.

Iccy Harrington competed in Formula Ford during the 1990s and today heads up the category for the Association.

Harrington identified the importance of providing the value for money, especially more than ever today due to the growing number of categories targeting the same competitor market base, such as the Toyota 86 Race Series and Hyundai Excels.

“We try and keep the costs down as much as possible,” said Harrington.

This is why the national series runs a seven-round calendar on a variety of events.

“Our aim is to maximise the racing for as little cost as possible, that’s why we compete on various different platforms,” he continued.

“We do like to do one Supercars round per year, it gives the young drivers an opportunity to operate at that level and it’s good for their profile, but the costs jump up so much.”

First, there is a championship registration fee of $1600, though an early bird offer cuts that price down to $1400. If a competitor completes less than three rounds a season, a round-by-round $250 fee applies at each.

Due to the different event platforms the category races on, entry fees vary.

At a Victorian State Circuit Racing Championship round, the entry fee is $415 but at a Supercars event this jumps to $1650. If a garage is added, the cost rises by at least $350, though this varies from venue-to-venue.

A weekend includes Friday practice at an extra cost of $210, but again this varies, followed by a 20-minute qualifying and three races.

Tyres is a constant as national competitors are required to purchase eight sets throughout the season, one per round and two at the opening event. This is done to further save costs, as tyre buffing was becoming a problem within the category.

“Competitors have to buy eight sets of tyres, which eliminates anyone messing around with buffing,” Harrington told Auto Action.

“If you don’t control it, it gets out of hand and the costs get ridiculous. It was a tough thing to decide on because it locks competitors into eight sets a year, but it puts so much control on the rest of the aspects.”

A set of Yokohamas cost $1016 a set.

Another cost-cutting measure is the free supply of lubricants as part of a deal with Castrol, which was to begin this year after a long association with Shell.

Harrington explained that a major recent development in the category has been the technical alliance between the bigger teams and father-son operations.

“A privateer aligning with an existing team through a technical alliance is a popular way of competing and managing costs, by doing all the labour-intensive work themselves, then getting someone experienced to oversee,” he said.

However, these big teams offer predominantly arrive and drive national programs, with the top-tier approximately costing around the $150,000-$200,000 mark. This is a complete package consisting of car rental, maintenance, a dedicated mechanic and engineer, catering, accommodation, car transportation, testing, tyres, entry fees and much more.

The next rung is around the $120,000 mark, but the package of support is not as comprehensive, though still includes the on-track components such as testing, entry fees, mechanic and engineer, tyres etc.

A State-level program is more accessible at $65,000 for five meetings and six test days.

Accident or engine damage due to negligence are not included in these costs.

Prizes are offered at the end of the year to the top three drivers in the national title.

The winner receives a Porsche Experience test day in Queensland with leading Carrera Cup team McElrea Racing, place second a day at Norwell Motorplex coached by Paul Morris, and third prize is a Freem motorsport clothing package.

The pole position award is a $200 Freem voucher for both the Duratec and Kent class.

Harrington believes the costs involved in the category are just right now but says increases will be hard to avoid.

“We’re always keeping an eye on it and we don’t want it to get higher than it is now, it’s in a good place,” he explained.

“It’s inevitable that prices (will) creep up. A few years back we changed around a lot and reduced costs, but they’ve crept up a little bit the last couple of years.”

Interested? The next step is to purchase a car.

There are two Formula Ford manufacturers that dominate the Australian scene, Spectrum and Mygale, while a smaller company in Sydney Listec is also making its mark.

Enter Mike Borland. His Australian designed and manufactured Spectrum chassis has won multiple titles worldwide, plus launched the careers of many racing stars.

To buy a new Spectrum chassis you would expect to pay $75,000-$80,000 for a rolling chassis and this includes everything needed to hit the track except the Duratec engine, which for a new unit costs $20,000.

The engine is a controlled unit sourced from Victorian-based Cylinder Head Innovations, which also handles the rebuilds.

“It’s basically supply an engine, pay the price there, have a seat and have a day Winton, then off they go,” explained Borland to Auto Action.

“It’s a complete rolling, drive out the door solution.”

Value can be found in the second-hand market, with a title contending late model chassis priced for between $45,000-$55,000.

But Borland advises that a car that is priced lower than that could need an engine rebuild.

“If you’re going to buy a used car, if the engine’s done its three years and it needs a rebuild the next year, you might pay $40,000 for the car. If the car has an engine that has just been rebuilt, prepare to pay more,” Borland advised.

“An early, early Duratec can be bought for the $30,000 mark, but those need a lot of work though they are good state level cars.”

The importance of all this is clearer when the cost of a rebuild is revealed.

“The things that change the price of the car is the engine,” said Borland.

“You’d probably get two-three years out of an engine rebuild unless you do something wrong. Engine rebuilds are expensive at $9000 but you only do it every three years.

“We budget $3000 on engines a year now, however back when I ran Mark Winterbottom, we budgeted $24,000 on engines, so that’s how good the Duratec is now.”

The tight regulations around engine development is where this large cost saving has been found.

“When we came up with the rules for the Duratec, we were pretty strict with the rules, so you didn’t have to spend hours and hours on the dyno,” Borland explained.

“There is a really small window that you can run with your exhaust system.

“We’re running the same system that we ran in 2006 when we built the first car.”

Moving onto the consumables, Borland Racing Developments change brake pads every meeting and test day, so a national competitor uses 13-14 sets a year at $150 each, provided by Ferodo. State competitors expect to use 10-12 sets a season.

National runners use two sets of rotors per season, state racers again won’t go through the same amount. These sets are made in-house by Borland and cost $200-$250 each.

The purchase of new tyres is not a requirement for state competitors, so six sets will be used across the season as well as for testing.

“The Yokohamas are quite different to drive on than the Avons because they are road radial tyre and stiff in the sidewall. They require a bit of a particular driving style that takes people a bit of time to get used to,” described Borland of the tyres.

“The driving style is very similar to a Supercar where they have to really stop the car and lean on the tyre in the corners a lot, so it’s actually good training for Supercars with the tyres they are on and the driving style required.

“Dollar per mile though they are just fantastic.”

The four-speed Hewland dog box with open diff is largely bulletproof, but because of the tyres being heavier, it is harder on the drivetrain. A development in the gearbox is Borland’s diff carrier, which further enhances reliability and is run by most teams through the field.

A downside is the $20,000 price of a new gearbox, though a rebuilt item is just as good.

“When we install one into a car it is generally a rebuilt second-hand gearbox with all new internals, because it’s way cheaper to do that than buy a new one,” said Borland.

Borland works through a routine when maintaining his fleet to ensure there are no failures during race meetings.

“We generally do things on a three-meeting cycle, so we’ll pull bits apart and do crack testing on components because we don’t want things to break,” he said.

“We’ll crack test the input shaft, driveshaft and a couple of other components in the drivetrain. We try to make the cars less resistant, so we don’t run seals and wheel bearings, so we need to service those and uprights regularly.”

Borland’s next rising star is New South Wales driver Cody Burcher, who with his father Shane has contested the past two Australian Formula Ford titles.

Burcher senior is very hands on, completing the maintenance and preparation himself, while receiving aid from Synergy Motorsport on race weekends in terms of data and set-up.

Burcher purchased a chassis for his son with the help of Borland three years ago for $45,000, then altered a few items to better suit their needs, costing a further $2000.

Support from Borland is provided at every meeting through a parts truck, but Burcher also has a small selection of components that are generally needed throughout the weekend.

“I’ve always been independent so I keep a small inventory of parts such as control arms, push rods, gears, dog rings, clips, bolts and springs, that (can) get you out of trouble on the day,” he explained.

Burcher outlined the tie-in with Synergy Motorsport.

“It’s purely data,” Burcher said. “Last year I took over preparing the car completely, transporting it, but when we get to the track Justin [Cotter, team owner Synergy] scales it and set it up. If something needs to be changed, Justin tells me to do it, so I handle that. Justin then takes over helping Cody with his driving through data.”

This comes at a cost of $1200-$1500 depending on the round.

Servicing is no problem. Burcher shares the same sentiments that Borland holds in advising that a set of plugs and leads might be needed at the start of the year, then a change of oil and filter halfway through the year, and that is really all.

Dog rings and gears is where serious money can be spent Some competitors may spend up to $1200 on gears but the Burchers only go through one gear and dog ring per event. The clutch costs $200 but is very sturdy.

Prep for each event takes roughly a day, but if it is a major service, then expect to at least double that time.

“If it was just a smaller prep it takes me eight hours by the time you do a wheel alignment and a few other items,” Burcher said.

“If it was a big one like wheel bearings or clutch or change the thrust bearing in it, you’d double that to 16 hours, with that being checked every 30-40 hours.”

Burcher estimated that 40-litres of fuel is used across a race weekend, purchased through Race Fuels at a cost of $60 over the course of a race event.

At $6000 per round and a budget of approximately $42,000 a season, the Burcher’s are almost frugal but frontrunners, nonetheless.

“You don’t have to be with a big team, you don’t have to do that. You can be a father and son team, plus have someone there to help you on the day with data,” Burcher advised.

“There are heaps of people around, but they don’t ask, they just assume you have to go with a team and pay big money to do it.”

Cody Donald is another participating in the series as part of a father-son operation and noted that an onboard camera and radio device are required at the national level.

“A GoPro camera for national events is compulsory at a cost of around $400,” said Donald.

“Radio communications are also a necessity to speak to the driver and communicate when (there are) incidents are out on circuit.”

A radio set-up costs approximately $2000.

Formula Ford remains one of this country’s strongest development pathways and the work undertaken during the past five years has led to the category’s rejuvenation.

And for those on a tight budget or just wanting a bit of fun, cost-effective racing, the Kent Class is ideal and surprisingly competitive with the Duratec cars.

COST GUIDE

The Traditional Pathway – Formula Ford

SERIES REGISTRATION

$1400 early bird, $1600 otherwise

ENTRY FEES

Vary between $415-$1650 depending on event

CHASSIS PURCHASE

Brand new $75-$80,000, used $30-$55,000

ENGINE

Control CHI engine $20,000, rebuild $9000

GEARBOX

Hewland 4-speed dogbox $20,000 new, used $6000-$12,000

TYRES

Yokohama AO48 $1016

BRAKES

Pads $150 each

Rotors $200-250 each

SEASON BUDGETS

National

Professional Team: $120-$200,000

Father-son: $40,000-$50,000

State

Professional Team: $65,000

Father-son: $20,000-$30,000

ENGINEERING PARTNERSHIP

$1200-$1500 per round

REQUIREMENTS

Radio $2000

GoPro $400