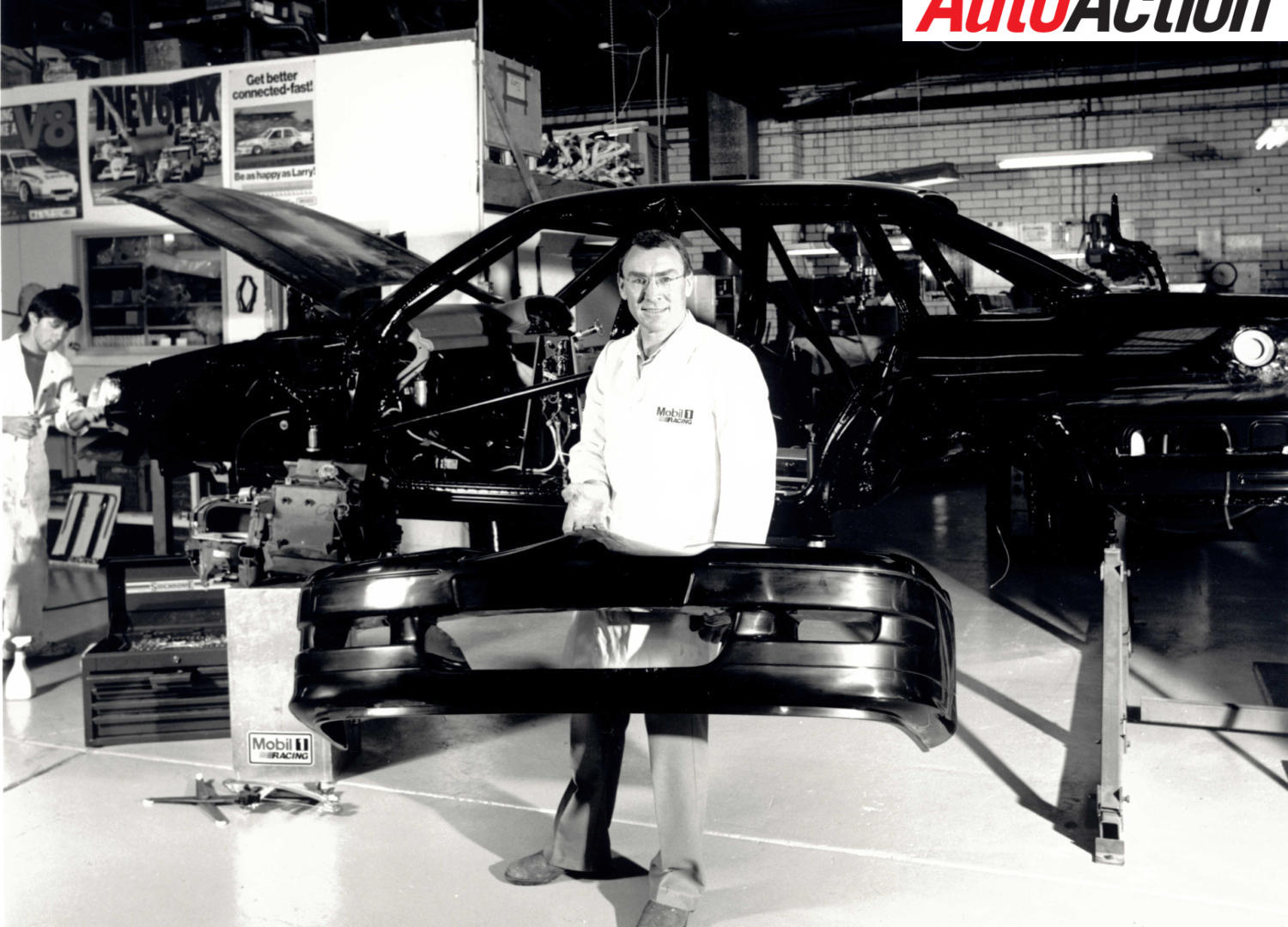

PERKINS’ 1991 MOBIL 1 HOLDEN GROUP A COMMODORE BUILD

In 1991 Peter Brock returned from the wilderness to Holden.

After a dalliance with BMW and Ford he brought along his Mobil sponsorship, and Larry Perkins’ – Perkins Engineering – Moorabbin based operation who built, prepared and ran two cars. The old firm was back together again.

In Godzilla’s year, Jim Richards won the ATCC in a Nissan Skyline R32 GT-R from youthful teammate Mark Skaife, by five points. They won the Bathurst 1000 that year too.

Brock was the best placed of the two Mobil 1 Racing entries, finishing sixth in the ATCC without taking a round win.

While the pickings were slim, it’s interesting to have a look at Larry’s superb VN Commodore SS Group A SV’s – in build – before the season commenced.

Former long term Auto Action contributor, and later founding partner of Motorsport News, Tony Glynn, wrote this wonderfully detailed piece – truncated just a smidge – about the build of the cars in Auto Action #518, published on February 15, 1991.

Team Mobil 1 Conference of War at Sandown in 1991.

VL to VN

Based upon the successful 1990 Perkins VL, the new VN project extends the evolutionary process and, as such, does not represent a giant leap into the unknown: it’s merely a further refinement of known technology and aerodynamics.

Perkins makes no secret of the fact that his VL “was the quickest. It was the most refined and had the most development spent upon it. It was still part of the V-series of Commodores improved over the last eight years and has been developed to an enormous extent. That’s what makes racing cars go quicker. On some of the circuits last year, it was a very quick car and there’s no doubt about that.”

Given a normal road-car doesn’t possess the required torsional rigidity to go racing, the key to a compromise chassis’ success must, of necessity, be related to the robust integral roll-cage. The current Perkins cage is not entirely dissimilar to that developed five years ago and the resultant gains in torsional rigidity have, therefore, been only minimal over the intervening years. Larry feels that “the rigidity issue is not a weak link with the car. Five years ago, traction was the problem, but we’ve largely overcome that now and we’ve increased traction enormously.”

“Certainly, the VN is assembled differently from the VL, particularly where the front bulkhead and dashboard are concerned. But that hasn’t caused us the slightest problem. We weld the bulkhead in, as opposed to the production gluing process. But we have the same degree of rigidity in the body with the VN as we had with the VL: so we’re not starting behind the eight-ball on that score.”

Rear end

Incremental changes and attention to detail result in increased performance for race cars and, in the case of the Commodore, traction. Race-shop preparation and attention to detail are the forte of Perkins Engineering and the live rear-axle reflects this philosophy.

A four-link rear with a Panhard rod and coil-over shocks is, superficially, a straightforward workmanlike set-up that few casual observers would hardly consider to be on a par with an independent rear-end. While acknowledging this view, Perkins also points out that “On smooth tracks, the need for an independent suspension is not as high a priority as you may immediately think. On rough tracks like Mallala, we do suffer from the design of our rear suspension. Overall, though, the trade-off isn’t great and the compromise really isn’t a bad sort of a suspension.”

The Harrop Engineering adjustable-camber rear-end may rate as the only genuine quantum leap in Commodore technology that really produced worthwhile gains in traction, a fact Perkins freely acknowledges. “Ron developed his set-up several years ago and its proved to be utterly reliable, which is of critical importance. There’s been no need for design changes and it has, indeed, given us the single biggest boost in improved lap times.”

“The manner in which you spring the rear-end is not really critical, but we do use coil-overs. Developments in shock absorbers for Touring Cars aren’t really worth talking about, unlike Formula One. We can’t see a need to change from a very conventional gas Bilstein matched to the springs we run. If we were to change springs to a different rate, we may have to alter the shock absorber, but there’s really nothing startling going on there.”

Bolt for bolt, the VL live rear-end and suspension, and front uprights are swapped directly to the VN. A 9-inch Ford centre is the norm for Commodores these days, Perkins preferring the Richmond Gears crown-wheel and pinion running in an alloy housing produced by Ron Harrop: this latter item is considered a better component than its alloy American counterparts, also available locally.

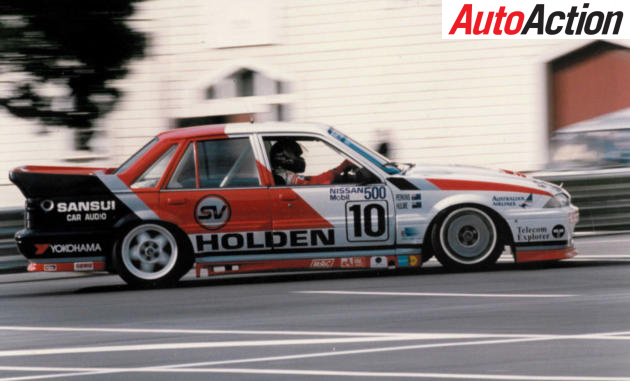

Perkins, VL SS Commodore, Wellington 500 1988. Second with Denny Hulme.

Perkins’ VN Commodore Group A shared with Thomas Mezera, DNF, Bathurst 1991.

Wheels and Tyres

Central to the traction issue for 1990 was the late-season fitting of 12-inch wide front tyres, heralded as the team’s most significant performance gain all year, rim supply difficulties meant smaller front rubber up till that point.

Perkins found that “it took some considerable time to get them produced in England, due to Dymag’s financial status. We’re not the Australian agents for Dymag, but we are by far the biggest buyer in this country.

“I own my own dies at the Dymag factory for magnesium Commodore wheels. I’ve sold over 200 wheels during the last four years and never experienced a failure. There’s never been a crack appear at any stage. In my opinion, wheels should have no tolerance for bad design, light weight or scope for being clever.”

“That’s why I went to Dymag, recognised as the world’s best producer of race wheels for Formula One, Indy Cars and so on. My mandate to them was that my Touring Car wheels have to be absolutely bullet-proof. I chose the · strongest, heaviest design, but they’ve never failed. They’ve been a real asset. There’s no compromise on wheels.

A road wheel isn’t a consideration.”

Front and rear wheels are the same, as are the tyres. Rims are 290 X 650mm 17-inch diameter units with a nominal 11-inch width: the overall tyre/rim width is 12 inches, right on the legal limit for the class. Any Commodore built since 1986 will accept the latest Perkins’ Dymag wheels, “as we don’t design obsolescence into the equation, the industry’s too fragile to cope with much change.”

Dunlop has become synonomous with Perkins over the years and 1991 looks to be no exception, at least until Bridgestone come up with a winner – well, that’s the view of those supposedly in the know. Clarifying the situation, Larry is well aware of the fact that “people are making assumptions that Bridgestone would carry on with their deal with Brock for 1991. But at the moment Bridgestone don’t have a tyre to suit the Commodore.”

“I’m unaware of the contractual arrangements Peter has with his own sponsors and I don’t know whether they are building a tyre or not. I do know we’ll have to be running the first race, if not the whole year on Dunlop tyres. All race teams seek to have a tyre contract and then seek to have a better one than the one they’ve got. I’ll be very happy if I can get the excellent Dunlops we were running last year on the car. If a tyre contract is going to be forthcoming, then that’ll be fine.”

(Ed – the pair were off the pace initially until Bridgestone produced a suitable tyre mid-year, when Brock, in particular became a challenger)

Dunlop’s current tyre was first tested by Larry at the Bathurst test-day last year and proved to be a remarkably good piece of rubber, subsequently carrying Larry to victory at the inaugural Eastern Creek enduro.

Weight of the Commodore is now down to 1250 kilos, whereas last year it was 1325 kilos. Mind you, the Sierra is also lighter – down from 1180 to 1100 kilos, the current FISA weight limit 1991 as is the 2WD Nissan (by 80 kilos). The 4WD Nissan GTR has suffered an increase of 35 kilos, topping out at 1365 kilos and, in Perkins’ view, “the mix of weights will enhance the level of competition. It’ll be more even, which is in the interests of us all.”

Tyre life is not necessarily directly linked to the perceived weight advantage, as Commodores were 1225 kilos back in the Group C days and managed to chew rubber up at a prodigious rate. That was a legacy of the inferior traction available at the time. These days, tyre life is more concerned with chassis set-ups than lower weights, though the current Commodore does possess a balanced tyre/weight combination – one that Perkins feels “may be marginally better than the Sierra, although the Ford has more power.”

Perkins Engineering 1991 500bhp 5-litre Holden V8 and 5-speed Holinger H-pattern manual ‘box. Note the length of the housing to put the weight towards the centre of the car.

Holinger gearbox

Peter Holinger’s 5-speed gear-box is to be carried over from the VL to the VN, with a 6-speed likely to appear later in the year (Ed – it was homologated in mid-’91).

Larry approached Holinger a couple of years back with the intention of commissioning a locally-built Getrag alternative: Fred ·Gibson, a long-standing user of Holinger’s gearbox components, also came aboard and the current common box resulted from that collaborative effort (Holden also becoming involved at one stage).

Main advantages of the local box focus upon the ready availability of parts, the seemingly bulletproof nature of the internals and the fact that production changes can be implemented within a matter of days. The Getrag was becoming a marginal prospect as power and torque outputs crept up, whereas the purpose-built, lightweight, non-synchro Holinger dog-box is logically engineered to admirably suit the Commodore’s characteristics.

Nonetheless, Larry has an order with Holinger “for a 6-speeder at the moment, but it won’t be available until June or so. It’ll be an even closer-ratio box and, as a result, we’ll be able to tune the car for all the corners.”

Engine

Torque is now up to 400 foot-pounds and horsepower 500, solid figures for an injected 5-litre iron motor that hasn’t departed too far from its road-going origins.

Its interesting to reflect upon the full-blown Formula 5000 engines, which only just managed to breach the 500 horsepower barrier. In this respect, Perkins sees the Holden “as an excellent base motor, made all the more impressive with the performance gains attributable to the Autronic fuel/ignition management system that Richard Aubert produced for me.

“Coupled with the Crane roller camshaft, the management system has been the biggest overall area of improvement where horsepower is concerned. We’ve then matched this with our own super-detailed approach to engine building, which has given us more reliability and more horsepower. There’s no magic anywhere. Its just a combination of many factors.” Bore : is a standard Commodore 4-inch, with a 3-inch plus 25-thou stroke, which equates to 4.99 litres.

An engine-capacity greater than 5-litres means that a FISA weight minimum of 1400 kilos applies to that class and, therefore, as the additional 75 kilos represents a considerable handicap, the Group A Commodore traditionally” runs the smaller 4.9-litre capacity fortunately without inheriting any measurable performance losses.

At last year’s Bathurst, Perkins went beyond his usual conservative ceiling for revs and hit 8500 rpm while chasing the ultimate lap time. Revs usually sit between 7500-8000 rpm these days, although a final figure is yet to be locked-in, “bearing in mind that we still have to be reliable. We apply very simple principles, much the same as would be found in any aircraft manual.

There are no prizes for not finishing. Most of our reliability comes from two areas – one is the inherent technical specification, presuming that we’ve done our homework correctly. That’s static.

The second is assembly and the handwork-that goes into assembly is the best. l’m very fortunate that we have in our engine shop three assemblers who are absolutely on top of the job. This area is headed by Neill Burns, who’s been with me for many years.”

Torque is considered to be “very good” from 5000 rpm upwards, the curve being very flat. In fact, Perkins doesn’t feel that “there’s a want for more torque. We’ve enjoyed very good support from Crane Cams over the years and their camshaft design has been one of the main factors responsible for the increased engine power, as I mentioned before. And we’ve remained reliable.”

A triple-plate AP sintered clutch has long been the team’s choice, carbon-fibre and moon-metal clutches are considered to be too expensive. “At ten grand Australian by the time you land one here, they’re too dear. We simply don’t have the budget. We didn’t have it last year and, this year; we still won’t have it to waste – even though the Mobil money is there. On a practical level, we don’t have the slightest problem with our current clutch. It may be fractionally heavier, but it doesn’t warrant the expense involved in the changeover, as seven engines requires $70,000 extra just for the new clutches.”

Front suspension and brakes

Perkins Engineering has always supplied its own front suspension uprights, based upon the standard Holden stub-axle and knuckle. Larry inserts his own axle-tube and uses his own-design hub and steering arrangement, with much of the machining work being carried out by Ron Harrop.

Considered to be fuss-free, the cars are built to be serviced once a year. Brake calipers are by Harrop and have stood the test of time. Although not quite as light as some of the trickier units available, Perkins prefers the local product: “we put them on once and forget them. Discs are also by Harrop. The master cylinder and pedal arrangement is exclusively our own and we enjoy a gain here, as we’ve paid careful attention to the mechanical operation where leverage is concerned in order to achieve the optimum effect. We supply these items with our customer cars, of course and they’re all hand-made in-house.”

Brock from Perkins at Sandown in 1991; VN Commodore Group A.

Body / Aero

Whether there is an implicit aerodynamic gain with the sleeker VN body shape remains to be seen. There’s no denying the fact that the Walkinshaw VL was promoted as an improvement over the standard VL shape, but not everyone agreed on the track. The VN claims have a familiar ring, but time will tell whether or not the shape actually equates to an improvement.

On this point, Larry concurs: “at this time, I can’t tell whether it will be better or worse. I must say, though, that the visual appearance suggests that it will be better than what we’ve had. Maybe the claims will be sound, this time.

“It would go against all the logic of engineering to think that the VN Will be slower. It may only be the same as the VL, but there’s a number of things to suggest that it will be quicker. Obviously, I’m expecting it to be quicker than the VL, but to what degree is the issue. I wouldn’t be surprised if we pulled another 10 kilometres per hour down Bathurst’s Conrod Straight, just due to the shape.

“The old VL would also have been quicker this year. We were five seconds a lap quicker at Bathurst last year, with exactly the same car as before and with-out the benefit of any regulation changes, I might add. Normal evolution always makes the same car go quicker. We’ll go quicker anyway, but some of that increase can be attributed to the new car.”

(Ed – Brock’s VN did 173mph/278.4 Kmh on Conrod, the VL circa 168mph/270.3, but the ’91 VNs were still circa 1.5 seconds a lap slower that the VL in 1990).

Commercial

The 1991 Mobil I Race Team of Peter Brock has come to Perkins Engineering with one special goal in mind – winning races. Larry Perkins will supply the state-of-the-art weaponry necessary to carry out the task and also take care of the peripheral issues; staffing, componentry and general logistics.

As Larry sees it, his area of responsibility is straightforward enough: “I’ll make sure that Peter’s team is absolutely what he wants, what Mobil wants and what we all want. We all have the same goals. “We’re following in the Euro-pean mould, where a driver secures the financing necessary to run a team. The driver doesn’t have the time to set up the workshops and engineering that’s so necessary anymore. We have a team of nearly 20 people here in Moorabbin and we’ve simply amalgamated with Peter. He retains the control of the area he handles best and has put his faith in my company’s technical capabilities. We have the best of both worlds, therefore.”

Holden’s rapport with Perkins Engineering has been ongoing over the years, Larry enjoying a number of short-term contracts to run the Holden Race Team until, ultimately, he stepped outside the Holden Special Vehicles operation completely last year and ran in his own right. But the Holden links are still strong and Larry’s now looking forward to enjoying a higher profile long-term relationship with both Holden and Brock – and guaranteeing that the highly publicised and widely acclaimed legendary Brock-Perkins-Holden triumvirate once more becomes an established force to be reckoned with, this time in the Group A Touring Car Championship.

Will history repeat itself?

(Ed – The results for the pair were not great against the might of the highly developed Nissan GTR’s, Ford Sierras and the likes of the BMW M3. The direct relationship between Brock and Perkins Engineering ended at the end of 1991. Peter Brock and his management team then started Advantage Racing.)

Image credits: Auto Action archives, Holden Motorsport, Tony Glynn.