PHIL IRVING : PRODUCTION BASED OR FREE DESIGN ENGINES?

One of Australia’s greatest engineering exports was Phil Irving, he of Vincent Black Shadow fame, and the rest. At home he found time to design Repco Brabham Engines’ 1966 F1 Championship winning 3-litre V8 and the Repco-Holden 5-litre Formula 5000 V8, in part the subject of this article.

Then Auto Action editor, Paul Harrington, commissioned quite a few pieces from Irving in 1974 – also an author of renown amongst his many talents – this one was published in Auto Action # 82 on April 4, 1974.

Some context is that this is only three weeks before Repco announced their decision to ‘phase out’ of motor racing engineering.

We hope you enjoy Phil (1903 – January 14, 1992), there is much more of him to come in ensuing months.

Broadly speaking, racing engines are either of free design, meaning that within the limits of engine capacity there are no restrictions whatever on construction, or else they are based on production components, usually with some degree of limitation as to what can or cannot be done by way of modification.

The 16-cylinder 3-litre BRM and Coventry Climax GP engines are extreme examples of the scale and at the other end, Formula Vee, where virtually no variations from standard are permitted to the engine itself.

In between there are many units consisting of a production cylinder block with modifications of a more or less drastic nature in the way of new or modified heads, crankshafts, lubrication system and so on, which comply with the relevant formulae.

The outstanding instance of what is termed the ‘stock-block’ engine is found in Formula 5000 in which the original block and cylinder heads be retained, but any amount of strengthening and re-machining can be done on the block and likewise extensive alterations mainly directed towards re-shaping the ports or combustion chambers, can be carried out to the heads.

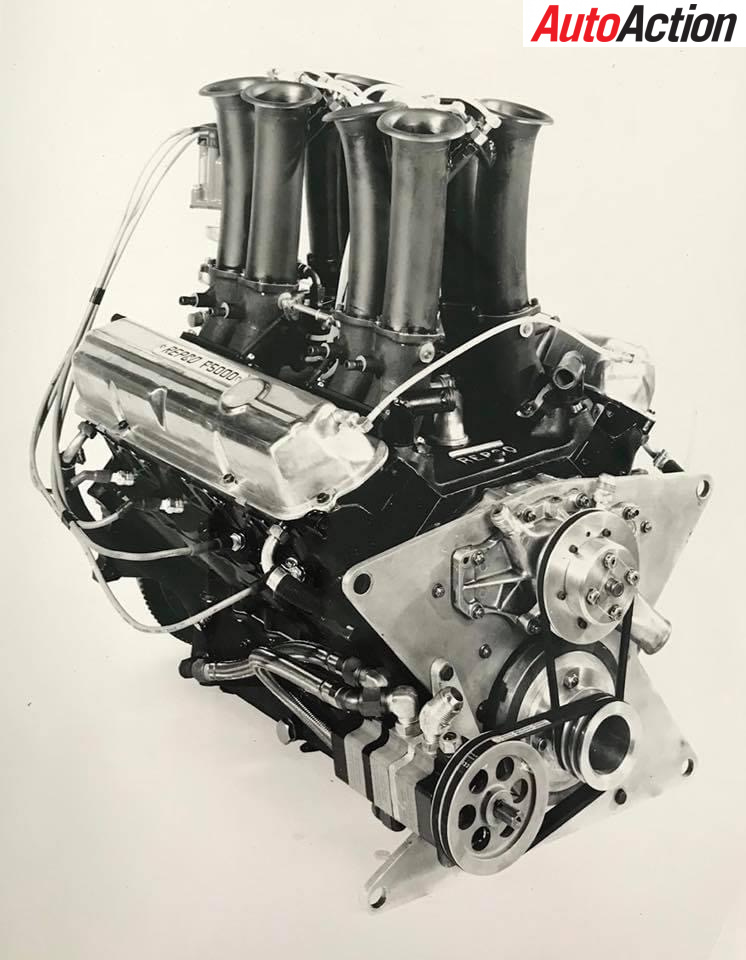

Repco-Holden F5000 engine. Circa 520bhp in ultimate 1974 flat-plane crank spec (Repco Ltd)

The camshaft must remain in its original position and the valves must still be’ operated by push-rods and rockers, though these are not necessarily of standard production pattern.

In fact, within these limits practically everything else can be modified or replaced, in order to gain more power, increase durability or save weight.

The underlying idea of the stock-block engine was to lessen the cost of a racing unit and also to ensure a virtually in-exhaustible supply of the basic ingredients, but it hasn’t worked out quite that way!

A competitive 5-litre engine costs about 7000 or 8000 dollars. There are, in fact, not many of them in existence, and the breakage of a con-rod bolt or perhaps a rod, almost invariably results in a catastrophe resembling mechanical harikiri, the motor disembowelling itself while still breathing!

Returning the wreck to full working order may cost about half as much as a new engine, usually requires a new modified block and takes up a lot of time, so anyone contesting a series such as the Tasman needs to have at least two engines on hand, with a third in reserve or undergoing repairs, if finances or the sponsors will permit.

Well, you might say, there must be something wrong with the things if they can only run a hundred miles or so without trouble. For a start, that estimate would not be altogether true. Some engines have covered much greater distances with only routine attention, such as changing head-gaskets or valve-springs, but these have usually not been handled by rev-happy pilots who feel they aren’t getting anywhere unless the tacho is nudging or even passing the 8000 mark.

You don’t hear much about them, whereas engine failure, even of a minor nature, or, perhaps due to a broken throttle wire or oil pipe and not to the engine itself, never escapes mention.

Phil Irving and chuckling Charlie Dean during a Repco PR shoot to promote their (Irving designed) Repco Hi-Power cylinder head for the Holden ‘Grey’ six cylinder engine, FE-Holden, mid fifties (Repco Ltd)

The fact is that when an engine is Intended for touring use with an output of less than 50 bhp per litre, excellent low-speed torque and a useful maximum of around 4000 rpm, the designer has to concentrate on cost and ease of manufacture rather than on sheer performance.

This means using the least amount of the cheapest material which will do the job, and this usually boils down to thin-wall iron casting for the block and heads, sheet-steel pressings wherever they can be employed, and nodular cast iron (SG) crankshafts, exceptions being the Rover and Leyland V8s in which the main castings are aluminium, giving a weight saving in the region of 150 pounds.

To increase the power output to around 500 bhp after suitable alterations to ports, pistons, camshaft, valve gear and the induction system, it is necessary to run the motor to 7000 or 8000 rpm. This means that the inertia loads on the reciprocating parts, crankshaft and block are quadrupled and moreover, they occur twice as often as before.

In other words, although you can get the power out of the top end, the bottom end just cannot stand the additional racket except with a little help from its friends, in the way of redesigned con rods (at up to $800 a set), heavier crankshaft castings or better still, steel shafts, four-bolt main bearing caps and modified lubrication passages and oil ways.

Even then you cannot always do what you want because there may not be sufficient room inside the crankcase, and it is not surprising that many hard-pressed components have to be changed as a routine precaution after a limited number of hours running.

It is not until any design has run for a season or two and closely inspected between races that these safety periods can be determined, and in that direction the Repco-Hoiden was originally at a disadvantage compared to the Chev which had a very long competition history behind it.

Extensive metal removal from ports to improve the breathing may bring trouble in its train through cracking, a recurrent affliction of Chev heads even now, but may be due as much to unequal thermal expansion as to the actual thinness of the port-walls.

The higher explosion pressures coupled with inadequate rigidity in the head and the top deck of the block tends to shorten the gasket life appreciably, but fortunately a gasket change is not a very protracted process. A two-man Repco team changed one for Johnny Walker in 40 minutes flat at Sandown.

However, any engine, stock-block or otherwise, has a rev limit above which it is not safe to run for long periods, and when the peak power rpm begins to approach this limit, trouble is not far from rearing its ugly head.

This was the position in the last days of the 2½-litre Coventry Climax which developed its best power at 6800, but was likely to burst at 7200.

As a result you either won the race or blew up in the attempt, depending on your luck and skill, and the same sort of situation was evident in this Tasman series, where time after time, cars which were being mercilessly driven to take and hold the lead right from the fall of the flag dropped out; leaving a more restrained driver to go the full distance and win.

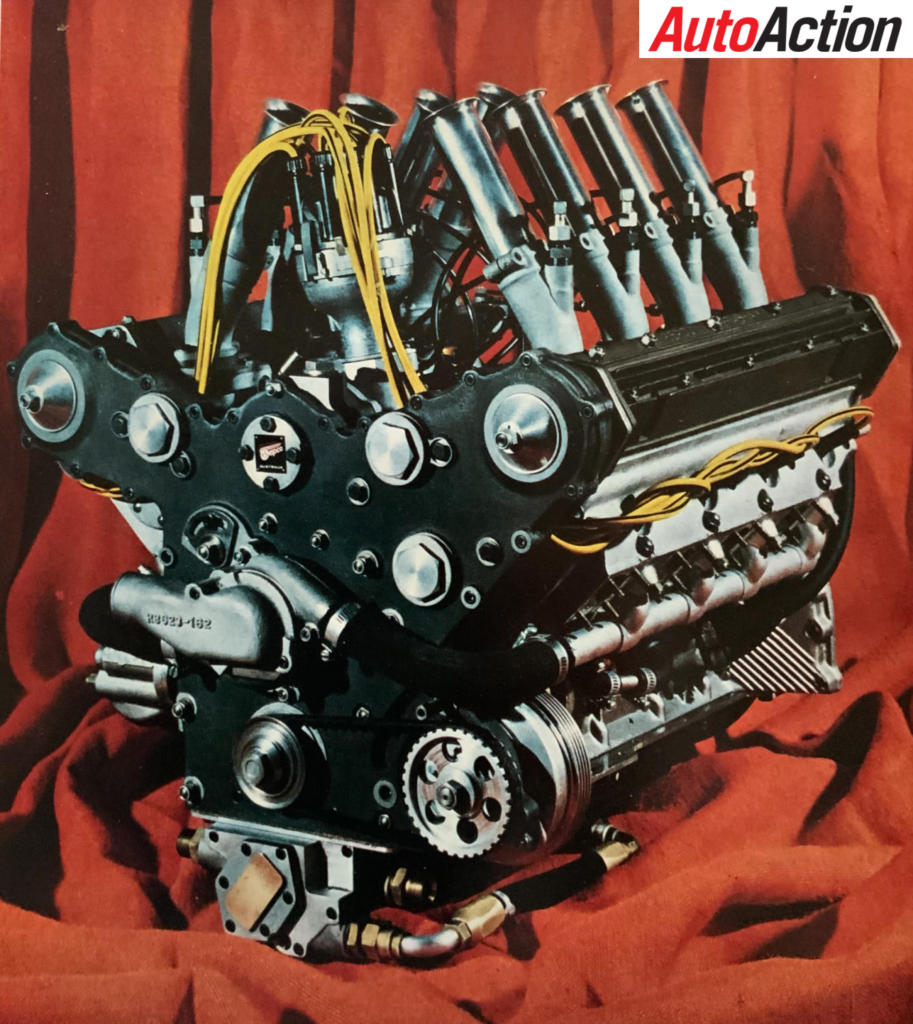

Repco Brabham Engines 1966 RBE620 F1 championship winning 3-litre V8 as fitted to Brabham BT19/20 – Brabham/Hulme driven – chassis that year. Irving designed and drew the engine using a much modified GM Oldsmobile aluminium F85 block as a base (Repco Ltd)

One of the reasons why the Repco-Brabham Formula 1 engines were successful in their first two seasons was that they could safely be run a thousand revs or more above peak power speed, so there was ample margin to cope with a missed gear change or to avoid making unnecessary up and down changes on tricky sections.

When designing a full racing engine with no holds barred, the designer knows what he is up against and can take the appropriate steps right from the start, putting strength and rigidity where it is vital and saving weight by employing exotic materials like magnesium or titanium with little regard to the expense involved.

The crankcase can be deep and made still more rigid by the addition of a cast sump, and free from the necessity for push-rod clearance and the head-studs can be correctly placed and anchored in substantial bosses.

The valve gear can be as complicated or as simple as one wishes and the difficult problem of scavenging the crankcase oil at very high speeds can be attacked.

In the end, you should be able to get a very powerful engine with good reliability at a much higher cost per unit, and if the cost of pattern and tooling equipment is taken into account, it will add greatly to the overall expenditure when only spread over a limited output.

That is where the shoe pinches in this country.

There is just not sufficient demand for a full racing motor of any particular capacity to make it a paying manufacturing proposition.

It could only be done on a prestige basis, in the same way as Fords’ commissioned the Cosworth 3-litre engine, primarily for the kudos which they would gain if it proved to be successful, and even then there would be little prestige to be attained unless the class in which it was competing was of world wide standing and not just a local invention peculiar to our own territory.

Photo Credits; Auto Action Archive, Repco Ltd, Jay Bondini and Nigel Tait Repco Collections,

Repco corporate portrait of Phil Irving circa 1969 – during the Repco Holden phase (Repco Ltd)