FORMULA 5000: DAYS OF THUNDER

Formula 5000: Days of Thunder

Half a century after Formula 5000 exploded onto the Australian scene, DAVID HASSALL recalls its painful birth and formative era, which was dominated by world-class driver/engineer Frank Matich.

Anyone who thinks that motorsport is currently blighted by politics should have been around in the 1960s at the dawn of commercialised racing. Crusty old gentlemen with pencil moustaches and gold-buttoned blazers controlled the sport, but they couldn’t even get their heads around the concept of having the engine behind the driver, much less gaudy sponsorship on cars with wings and treadless tyres driven by young blokes with long hair.

It was in this era that Formula 5000 was born – or at least ripped, kicking and screaming, from a reluctant matron – but it went on to become undoubtedly the best premier formula Australia has ever had.

At its peak, F5000 was vibrant, exciting and blood-curdling, with thundering projectiles that not only matched international Formula 1 cars for speed but challenged the ability of local tracks to contain them.

Even at its worst (despite how it seemed at the time), in the formula’s dying days, there remained a handful of dedicated racers providing modern, competitive, well-prepared cars driven in anger by champion drivers such as Alf Costanzo and John Bowe. No wonder it inspired the current S5000.

Australia and New Zealand in the 1960s enjoyed a comfortable relationship with the Grand Prix world in Europe. The Tasman Series provided a nice excuse for the world’s top teams and drivers to escape the European winter and race under the sun on an Antipodean adventure, so each year we would enjoy watching the likes of Jim Clark, Jack Brabham, Graham Hill and Jackie Stewart racing every weekend for eight weeks.

We could even afford the luxury of imposing on them an old 2.5-litre formula – abandoned by F1 at the end of 1960, along with front-engined cars – that required the teams to enlarge their usual 1.5-litre engines in the early ’60s or reduce their later three-litre units just for this two-month series on the opposite side of the world.

Of course, it couldn’t continue. As F1 expanded and became more demanding, the Tasman series became a luxury the teams simply couldn’t afford – and Australia couldn’t afford to continue with an outdated, expensive and anachronistic formula for the dwindling number of old-style patrons who provided the ever-depleted grids.

By the time the first cigarette-sponsored cars had dared to race on our shores, much to the disgust of long-time CAMS secretary-general Donald K. Thomson (CEO was much too mundane a title for the cravat brigade), there were only three competitive cars in Australia and it was clearly time for change. But to what?

An unholy battle wracked the sport for months in 1969 over whether to adopt F5000 – an uncouth stock-block monster invented by those crass Americans – or a more ‘pure’ two-litre car being promoted by the almighty FIA in Paris and also our regional neighbours to the north. There was even talk of a big Pacific Formula Championship that persisted for years without ever gaining traction – and which would never have worked culturally or commercially.

The entire sport in Australia split into two quite disparate camps in 1969. Reigning champion team owner Alec Mildren and his engine builder Merv Waggott, who was developing a four-valve two-litre four, led one side. On the other was the influential but divisive Frank Matich and his powerful backer Repco, which had been forced to abandon its F1 title-winning program with Jack Brabham and was now developing a stock-block race version of the new Holden five-litre V8 to challenge the Chevrolet unit that powered most F5000 cars in the US and England.

CAMS was philosophically inclined towards the traditional race engine route and initially declared the two-litre formula as the winner in July ’69, but such was the backlash that the governing body quickly retreated and did a very bureaucratic thing – it had a bet each way and chose both! The new Australian National Formula 1 (ANF1) would therefore accommodate both formulas, though time would soon enough see the F5000s predictably rule the roost.

Matich brought the first F5000 to Australia. He had canvassed the options in the UK, where the best racing cars were built, but was horrified by the big and heavy Lola offering, so instead went with his mate, New Zealander Bruce McLaren, who was making quite a mark with his own cars around the world.

McLaren held Matich in high esteem as both a driver and engineer, and in 1965 had asked him to come across to race in F1 and help Bruce with the Ford GT40 Le Mans program. If not for a huge sports car crash at Lakeside that prevented Frank from going to Europe, he may have become the Ken Miles character in the Ford v Ferrari movie.

As it was, McLaren commissioned Matich to take over the development of his first Formula 5000 car, based on an M7A F1 chassis and intended for sale around the world by production offshoot Trojan, because Bruce himself was too busy with F1, F2, Can-Am and road car projects.

The prototype McLaren M10A was sent out to Australia and debuted at Warwick Farm on September 7, 1969, initially fitted with a Chevrolet V8. But it was, Matich later admitted, “an awful pig of a thing”. Serious development work was required, but the M10A was still good enough for Matich and customer Neil Allen to dominate the 1970 Tasman Series in January/February, though a consistent Graeme Lawrence snared the title in his 2.5-litre Ferrari.

The full result of Matich’s dedicated development program for McLaren was revealed in July 1970 in the form of the M10B – built entirely in-house by Matich – complete with Repco’s new Holden-based engine bolted in the back. With it he finally won his first Australian Grand Prix, on his home track at Warwick Farm, but again the Tasman eluded him. Both Matich and Allen were narrowly beaten in 1971 – this time by another Kiwi, Graeme McRae, driving a similar Chev-powered car – but at least it was a 1-2-3 for the Matich-developed M10B.

Before the start of that year’s Australian Drivers’ Championship for the CAMS Gold Star, another honour that had eluded Matich, he took his Rothmans-sponsored car to California to contest the first two rounds of the lucrative US championship and stunned the locals by winning the first round and finishing second in the next.

Despite leading the championship and picking up about $12,000 in prizemoney – quite a sum considering a Gold Star race win paid only $340 – he had no interest in remaining in America and was quick to get home to his young family and growing business interests.

The motor racing scene in Australia was changing rapidly, though, with a clear shift towards touring cars (Moffat, Beechey, Jane, Geoghegan and co) and series production racing (with Bathurst and the Ford and Holden factory teams).

The new open-wheeler category also had to deal with the retirements of Neil Allen and Leo Geoghegan (from ANF1, later returning to dominate AF2), and the departure of its traditional open-wheeler patrons. And, with promoters increasingly unwilling to pay appearance money, drivers like Kevin Bartlett, Max Stewart, Alan Hamilton, Garrie Cooper and John McCormack had to secure commercial sponsors to survive.

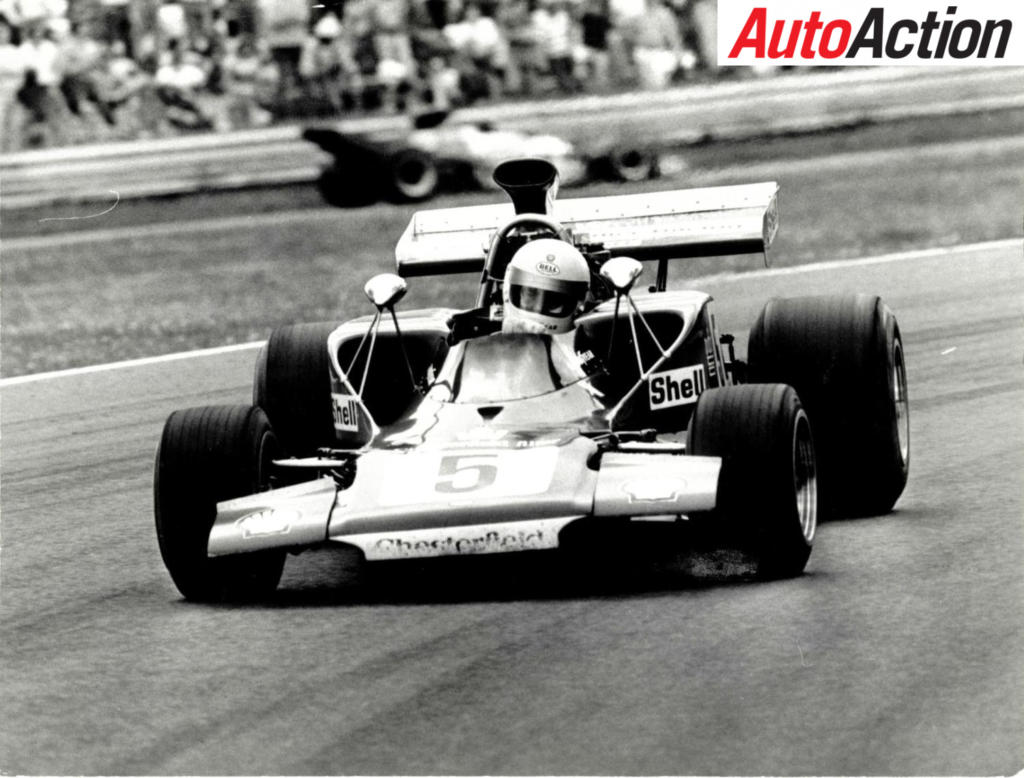

The ever-spectacular Kevin Bartlett powers around Warwick Farm during the 1972 Gold Star race in his superb Chesterfield-sponsored Lola T300.

Bartlett and Hamilton jumped in by buying Allen’s two McLarens – with Shell and BP money respectively – while Cooper designed and built a new Elfin, the Repco Holden-powered MR5, for himself and McCormack (eventually run under the Team Ansett Airlines banner), as well as Stewart. The new Elfin impressed on debut at Sandown in September 1971, but soon after Matich upped the ante considerably with his own new creation, the Matich A50, having abandoned the McLaren connection following Bruce’s untimely death the year before.

Matich proceeded to win a second AGP at Warwick Farm on the A50’s debut in November. However, his Tasman curse again struck and McRae pounced to score his second title in ’72 against a quality international field that boasted Mike Hailwood and Frank Gardner, who had joined Lola and introduced the revolutionary side-radiator T300 that began a decade-long dynasty for the British marque.

The 1972 season saw the formula blossom in Australia, with the appearance of new T300s for Bartlett and Bob Muir, and the entry of a young Warwick Brown in an old McLaren bought by his neighbour in Sydney, Pat Burke.

Matich was still the man to beat, though, and he finally won his first Gold Star award by concentrating on the local scene while Bartlett, Muir and Colin Hyams spent time chasing the gold on offer in America.

However, while Australia’s most highly regarded domestic driver did win his national Grand Prix and the Gold Star, he never won the Tasman, much to his eternal regret.

Graeme McRae won the Tasman then took his stylish GM1 to success in both America and England

In his last full assault in 1973, Matich was again beaten by McRae, who had followed his Aussie rival’s lead the previous year by designing and building his own car, the curvy STP-sponsored McRae GM1. It was a beautiful machine, and would soon bring him global fame and fortune with further success in America and England as well as at home.

That ’73 Tasman Series was also notable for the rise and near demise of 23-year-old Warwick Brown, who had graduated to a competitive Lola T300 under the guidance of technical guru Peter Molloy, with sponsorship from the Target department store chain.

He had shown glimpses of ability in the old McLaren, but in the T300 his bravery and growing touch were there for all to see – until one fateful day at Surfers Paradise International Raceway when he went off the road at high speed and bent the Lola in the middle, badly breaking both his legs. Brown was lucky to survive and spent three months in hospital. It would be another six months before he could drive a racing car again.

With no local races until September, five Australians – Matich, Johnnie Walker in a customer A50, Bartlett (Lola T300), Stewart (with his new Lola T330, a much-improved development of the T300) and Bob Muir (T330) – headed to the US to collect some of the fortunes on offer there. The L&M Championship offered some US$535,000 in total prizemoney, with as much as US$17,000 – the cost of a new racecar – for a win. Max Stewart was the highest-placed Aussie in 12th, a long way behind series champion Jody Scheckter.

Matich went well equipped with a pair of updated cars and, from mid-season, a new side-radiator model designated the A52, but his Repco engines were plagued by oil surge problems on the high-speed American circuits and he finished with little to show for his efforts. His wife had also fallen seriously ill and he arrived back from the US after only five of the nine rounds disillusioned, then put his three cars and race equipment up for sale.

John McCormack had remained home to prepare his seemingly outdated Ansett Elfin MR5 and narrowly snatched a maiden Australian Drivers’ Championship from the greatly improved Johnnie Walker, who was now driving a new Holden-powered Lola T330. But the Gold Star series had been a major disappointment, with slim fields and deserting promoters, and even the Warwick Farm circuit – for many years the bastion of open-wheeler racing in this country – had closed.

The 1974 Tasman Series had little international support – the VDS team of Peter Gethin and Teddy Pilette mostly dominated – and, although Warwick Brown returned to full strength with the Lola’s latest T332 model, the local scene was dealt a further blow when Kevin Bartlett smashed his hip and leg in a huge accident at Pukekohe in New Zealand.

Matich had reconsidered his retirement and built a new A53 for the Australian rounds of the Tasman, but just before his comeback race, he was seriously electrocuted on a boat. It was only the fact that he collapsed across the battery terminals, with a course of power keeping his heart going for 11 minutes, that he survived at all. Technically, he died that day in late January 1974.

Although Matich returned to the cockpit less than two weeks after this near-death experience, still with a hole in his chest, he wasn’t the driver he’d been. So when Repco suddenly withdrew from racing, he simply walked away from the sport.

Formula 5000 would survive Matich’s retirement and other challenges to enter a new era. The Lola era. But that’s a seminal story for another day…

Article originally published in Issue 1777 of Auto Action.

For Auto Action’s most recent features, pick up the latest issue of the magazine, on sale now. Also make sure you follow us on social media Facebook, Twitter, Instagram or our weekly email newsletter for all the latest updates between issues.