LONDON TO SYDNEY MARATHON: RACE OF AGES

London to Sydney Marathon: Race of Ages

It wasn’t quite round the world in 80 days, but the 1968 London to Sydney rally captured the imagination of the world at a time when hostilities between nations had eased and the popularity of the motor vehicle was growing significantly. What lay ahead for the 98 crews that started were 16,000km of brutal, car torturing terrain, but a real boy’s own adventure

By BOB WATSON

In 1968 conditions in England weren’t good, the Pound Sterling had been devalued, manufacturing was in a slump and an atmosphere of gloom pervaded the country.

Sir Max Aitken, chairman of Beaverbrook newspapers, which owned the Daily Express newspaper, called a lunch meeting with senior editorial staff members Jocelyn Stevens and Tommy Sopwith. The group discussed the idea to organise an event that would attract worldwide attention and provide an opportunity for to showcase the British manufacturer’s products.

The outcome was the London to Sydney Marathon, the greatest motoring adventure since the Peking to Paris race of 1907.

The Marathon quickly captured the imagination of car companies and sponsors globally, including the Australian press. Sir Frank Packer, chairman of Australian Consolidated Press, offered co-sponsorship from the Sydney Daily Telegraph, which was quickly accepted by Aitken.

The entry fee was set at £550. First prize was to be £10,000, plus a superb trophy consisting of a silver crescent and a golden globe of the world marked with the Marathon route, standing 72cm high and worth £500. Second and third placegetters won £3000 and £2000 respectively, with another £2000 for the highest placed Australian crew.

The event was open to four-wheel passenger cars with no more than six seats, and the station wagon derivatives. Commercial vehicles, motor homes and four wheel drive vehicles were not eligible. The mechanical specification was free, that is there were no restrictions to the modifications that could be made. The engine and body could not be changed during the event and these parts were marked at pre-event scrutiny of the cars.

All participants, from those organising the rally to car companies, fuel and tyre companies then swung into action. The organising committee was chaired by former racing driver and sailor Sopwith with another experienced rally competitor Jack Sears appointed as secretary. The committee included Dean Delamont (later to become Chairman of the Royal Automobile Club), Tony Ambrose and Jack Kemsley.

Various problems became evident, including the refusal of the Burmese (Myanmar) government to allow passage of the event, difficulties arranging transport of the rally cars from Colombo to Australia and the closure of the Suez Canal due to the Arab-Israel war.

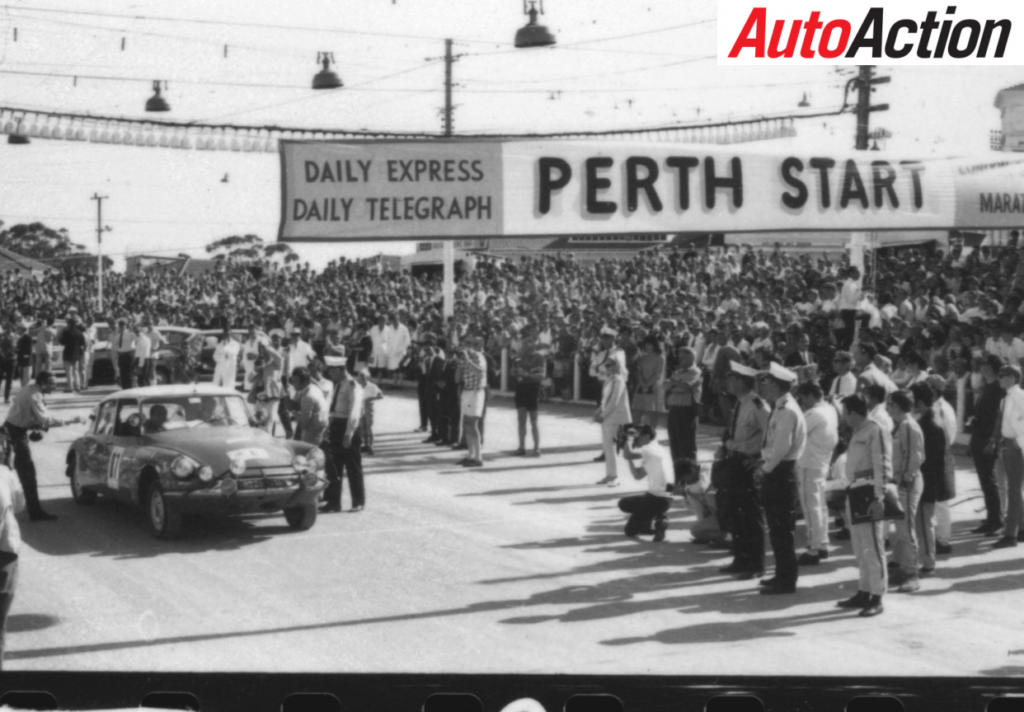

Entries started pouring in from around the world for the great adventure. The field was limited to 100 cars due to the available space on the liner Chusan, which was to take the cars from Bombay to Fremantle.

Entries were received from 14 different countries, with Great Britain (57) and Australia (18) in the majority. Others came from France (5), Russia (4), West Germany (3), Ireland (2) Switzerland (2), Holland (2), USA (2) and one each from Norway, Kenya, Poland, Italy and India.

The major car manufacturers were keen to be involved, sensing an opportunity to promote their products in the 11 countries the Marathon passed through. Ford Motor Company of Britain, Australia and Deutschland all entered teams, as did British Leyland, Rootes Group, the Holden (General Motors) company of Australia, Moskvitch from Russia and DAF from Holland. Strong factory supported private entries from Porsche, Citroen and Volvo while a second tier of privately sponsored private entrants running cars similar to the factory entries, no doubt hoping for factory help if the big guns faltered.

The massive task of planning the 16,000 km course was completed in time to allow teams to do a reconnaissance if they wished, or could afford it. The Castrol oil company sent an experienced crew to compile route notes for the teams the company was sponsoring. Tyre and fuel dumps had to be set up in remote locations across the world, and servicing to be organised. Local car clubs were recruited to man control points. It was a massive organisational task.

Ford entered a team of four Ford Escorts led by Roger Clark and Ove Anderson, while Dieter Glemser and Martin Braungart headed Ford Germany’s three car Ford Taunus attack.

The strongest driver line-up appeared to be the British Leyland entered cars of Paddy Hopkirk/Tony Nash/Alec Poole, Rauno Aaltonen/Henry Liddon/Paul Easter and Tony Fall/Mike Wood/Brian Culcheth in Austin or Morris 1800s, backed up by a similar 1800 from BMC Australia for Evan Green, ’Gelignite’ Jack Murray and George Shepheard.

Entries of Citroen DS21s for Lucien Bianchi/Jean-Claude Ogier and Robert Neyret/Jacques Terramorsi had factory support, as did the Porsche 911Ss of Pole Sobieslaw Zasada/Marek Wachowski and East African Edgar Herrman/Hans Schuller, and a Rootes Motors entered Hillman Hunter driven by Andrew Cowan/Colin Malkin/Brian Coyle.

The surprise packet of the event were the three Harry Firth-prepared Ford Falcon entries from Ford Australia. The big cars, along with the Daily Telegraph Holden Monaros headed by David McKay were regarded by the European experts as being too large and too heavy for the journey.

The marathon started at London’s Crystal Place sports complex in front of a crowd of 80,000 people. The field of 98 cars lined up, made a colourful scene adorned with advertising stickers, kangaroo bars and in the case of the two factory prepared Porsches, cage like constructions to support oil coolers, spare wheels and deflect the dreaded ‘roos.

At 2pm on November 24, the Ford Cortina GT of Bengry/Brick/Preddy left the dais first to get the rally underway.

The route travelled from London to Paris, and then across Europe into Turkey, with check points at Turin in Italy and Belgrade in Yugoslavia. This was easy travelling, although tiring for crews. However, in Turkey poor roads and the presence of slow moving smoke billowing trucks, sometimes three abreast added a dangerous element.

The first serious competition came in Turkey. The stage from Sivas to Erzincan was 175 miles (283 kms) of loose dirt, gravel, and mud, whilst rising to 7000 feet was to be covered in 2h 45m. Clark stamped his authority on the event by being fastest, six-minutes late, averaging nearly 100 km/h.

The pursuit of Clark was headed by the Ford Taunus of Gilbert Staepalare, Paddy Hopkirk’s BMC 1800, Glemser (Taunus) and Lucien Bianchi (Citroen). Fastest Aussie was Bruce Hodgson followed by Ford teammates Firth and Ian Vaughan. Best Holden was Barry Ferguson.

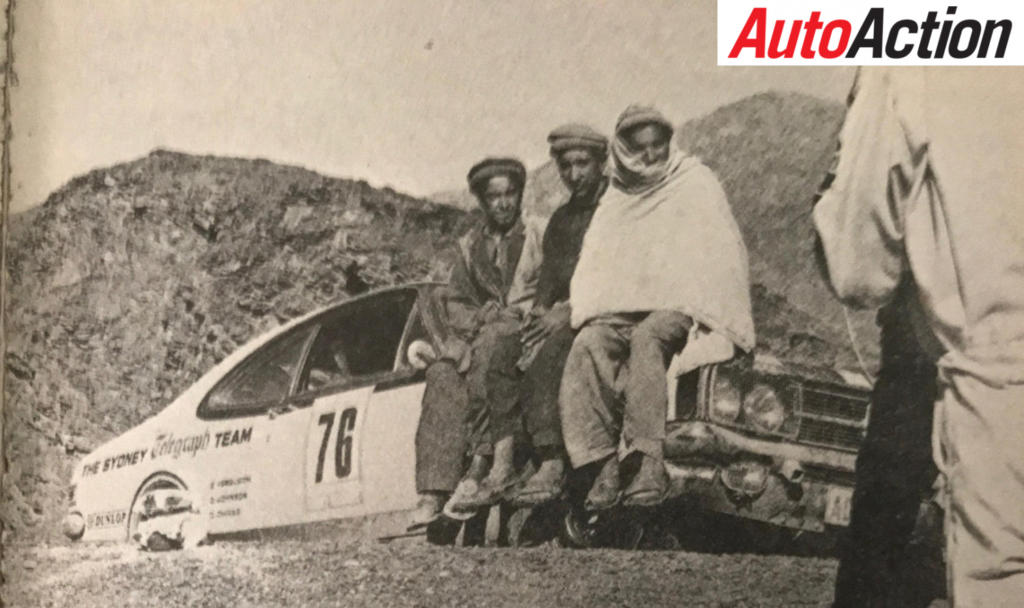

The next test was across the Lataband Pass to Sarobi in Afghanistan. Clark was fastest again but was matched by Hopkirk and Bianchi and Staepalare. Evan Green was best Australian with 8 minutes lost, Firth‘s Falcon and the Holden Monaros of Doug Whiteford and Barry Ferguson were close behind.

A long but non-competitive run to Bombay followed, although crews were tested by the erratic traffic and the crushing crowds. There, the surviving 72 cars were loaded onto the SS Chusan for the 10-day trip to Fremantle with the Aussies telling stories of monster kangaroos and six-foot-tall Bunyips.

The drama exceeded expectations in Australia as the Western Australian Police made themselves known by booking competitors for having sirens and flashing lights fitted to the roof. Generally making themselves unpleasant.

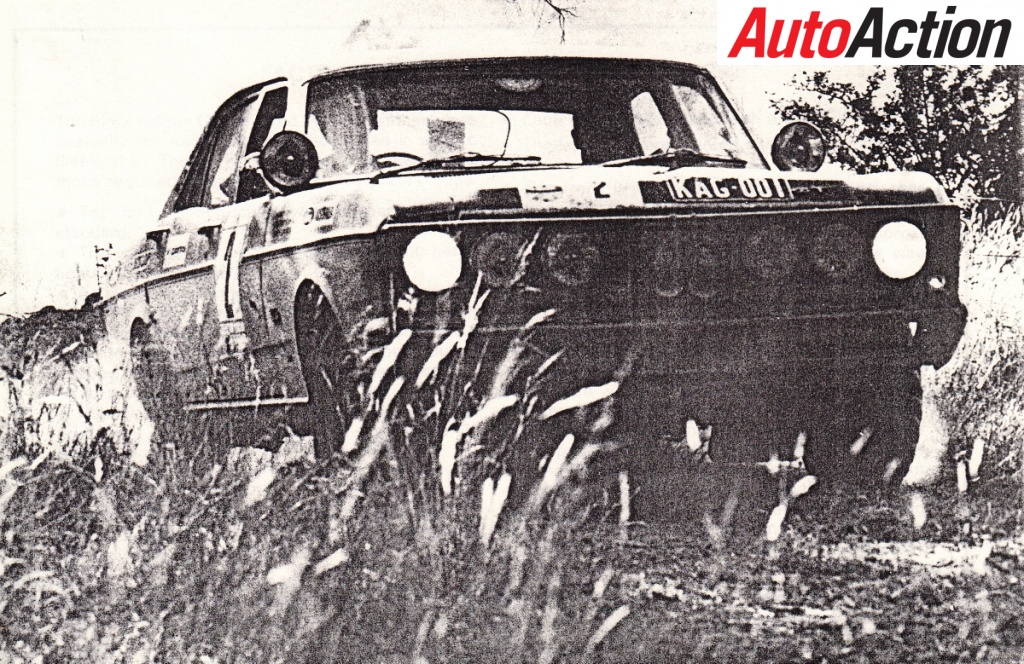

The course headed North East from Fremantle to the gold mining ghost town of Youanmi and then south to Marvel Loch. The first test was from Marvel Loch to Lake King, 190 km.

The organisers provided the following information in a bulletin: “The countryside is undulating and from each ridge the straight road ahead can be clearly seen, but on the crests of certain ridges the road takes a sharp bend and these well concealed hazards may prove the undoing of a driver who is not concentrating”.

The latter part of the section proved extremely testing, deteriorating to rocky outcrops and high ridges in the centre of the road, which was very narrow with cars brushing the scrub on each side.

The dust was thick, which gave the early cars a big advantage. Fastest were Clark’s Cortina again, joined by Staepalare’s Taunus and Bianchi’s Citroen. Vaughan (Falcon), together with Cowan’s Hillman Hunter were again close behind as cream was beginning to rise to the top.

A long run of 1460km across the Nullarbor Plain to Ceduna was no problem for the leading cars, Bianchi in the amazing Citroen averaged 97 mph (157 km/h) over the rough gravel. However, the next section from Ceduna to Quorn in the Flinders Ranges produced drama as Clark’s Cortina had burnt valves after the long high-speed Nullarbor crossing, and was running rough. In a magnificent sporting gesture his teammates Ken Chambers and Eric Jackson gave the cylinder head from their Cortina to Clark, and it was fitted at Port Augusta. They had been running ninth at Fremantle. Clark booked in 14 minutes late at Quorn after a hair-raising drive over the Pichi Richi pass.

The Flinders Ranges caused some havoc. Again, from the Organiser’s Information Bulletin: “Competitors turn right to cross the Elder Range by a scenic track (now the Moralana Scenic drive) punctuated by creeks which vary in width from a few metres to several hundred. Indeed, at times competitors will wonder whether they are expected to motor up river beds rather than on the intended roads”.

One of the leading group, Evan Green in a BMC 1800 suffered rear wheel bearing failure while running fifth. The failure occurred not long after Green had allegedly helped Andrew Cowan’s Hillman Hunter back on to the road after an ‘off’. George Reynolds rolled his Monaro over in sand near Mingary with the crew ending up in hospital, and Ferguson’s Monaro broke a shrink ring.

Through Broken Hill, Menindee and Gunbar the field reached Wangaratta in North Eastern Victoria, facing a testing time over the Great Dividing Range. The Edi to Brookside stage followed a little used State Electricity Commission road over Goldie’s Spur, a rough steep mountain track with massive drops over the side. Zasada in the Porsche was looming as a threat, dropping only one minute, with Hopkirk close. Clark was back on form, whilst Bianchi, Staepalaere, Aaltonen and the consistent Ford Falcons of Vaughan, Hodgson and Firth on continued to press.

The course then climbed over Mount Hotham to Omeo, where further points losses were incurred by the leaders. Zasada and Staepalaere were flying, as were Bianchi, Cowan, Clark and Paddy Hopkirk. Vaughan did well to be first of the Falcons.

At this point the leaders were Bianchi on 34 points, Clark on 39 after a brilliant recovery from his burnt valve problem with Hopkirk and Staepalaere tied on 40. Cowan’s Hillman was on 46 and Harry Firth in the leading Australian Falcon 49. The final stages of this mad dash across Australia could not have been scripted by even the most creative fiction writer.

Not long after leaving Omeo, second placed Clark broke an axle, and spent valuable time fitting one taken from a local’s car. After the Ingebyra stage Bianchi was still clinging to a slim 4 point lead over Staepalaere’s Taunus with Hopkirk and Cowan not far behind.

Then on the final Hindmarsh stage over the “Big Badja” Firth, lying in sixth had rear axle problems and was forced to wait for one of the following Falcons carrying a spare.

But still the drama was not over – Staepalaere, running second, hit a cattle grid post and broke a steering tie rod, costing him any chance of a high placing. His misfortune allowed Cowan into second place.

At Hindmarsh Station the rally was virtually over, Bianchi had proven that he and the Citroen were the best and there was no more competition.

But then the unbelievable happened.

On the final transport stage to Nowra, a spectator’s car, travelling legitimately against the direction of the rally on an open road, collided head on with the Citroen, driven by Ogier while Bianchi slept.

The super light Citroen was crushed by the impact and Bianchi was badly injured and rushed to hospital. It is suspected that Ogier, in his exhausted state, reacted as he would have done in Europe, and pulled to his right to avoid the oncoming Mini. The two people in the Mini were also hospitalised and their car totally wrecked.

Paddy Hopkirk was first on the scene and stopped to check the accident scene. The 56 survivors from the 98 who started at Crystal Palace had driven non-stop for 67 hours across Australia.

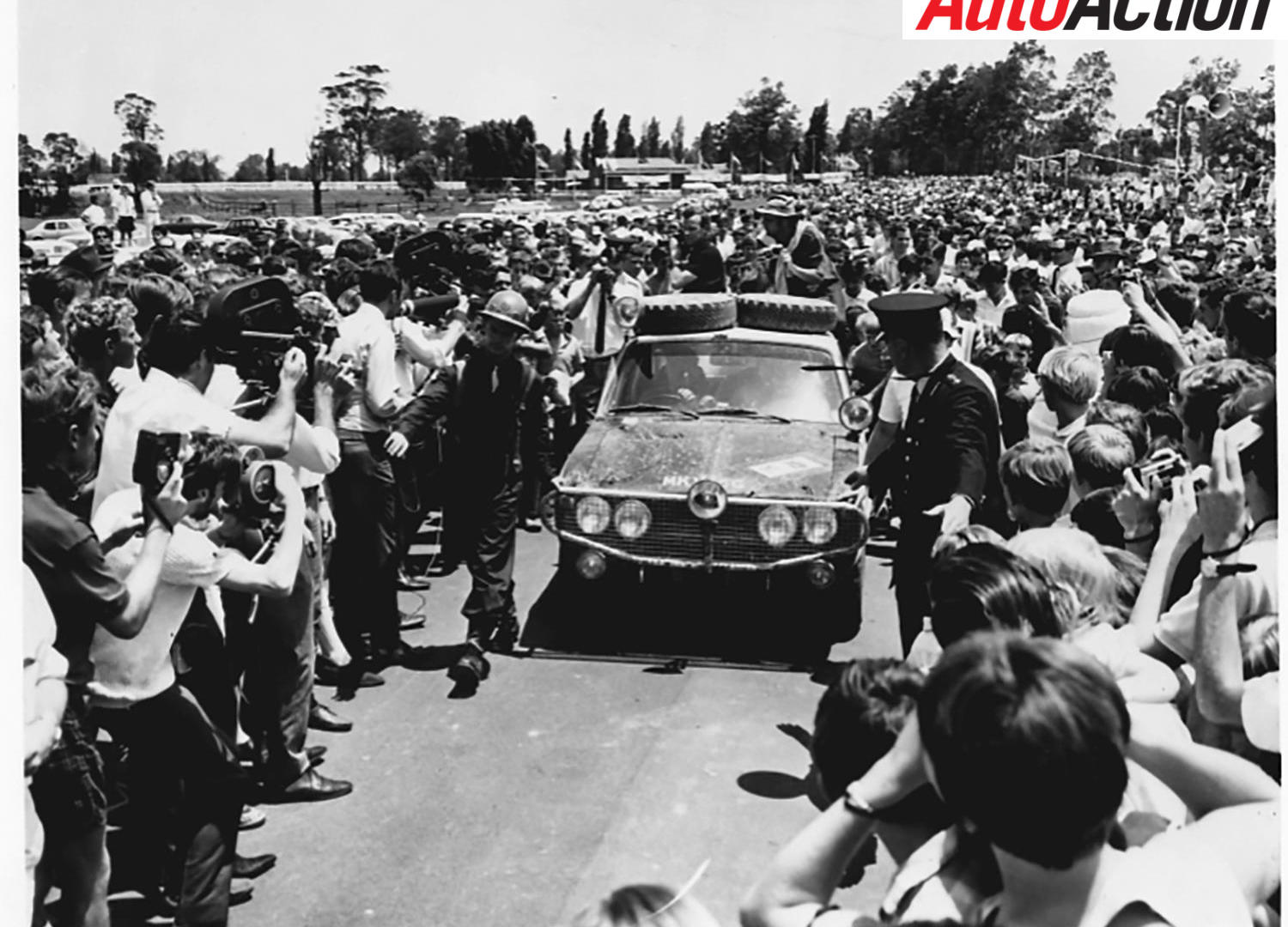

Cowan drove to the event finish at Warwick Farm racecourse in Sydney, no doubt happy that he, Brian Coyle and Colin Malkin, and the well-prepared Hillman Hunter had won the world’s most amazing rally, though subdued by Bianchi’s tragedy.

He proved his victory in the Marathon was no fluke by winning the only other “real” marathon, the 1977 30,000 km Singapore Airlines London to Sydney rally in a Mercedes Benz. He won five Southern Cross rallies for Mitsubishi and is acknowledged as the greatest long distance rally driver of all time.

Post-rally, Hillman were besieged by orders for Hunters to the point where they were embarrassed by lack of stock.

Sir Max Aitken’s brainchild had done its job!

Article originally published in Issue 1750 of Auto Action. Read the rest of the four-page feature here.

For Auto Action’s most recent features, pick up the latest issue of the magazine, on sale now. Also make sure you follow us on social media Facebook, Twitter, Instagram or our weekly email newsletter for all the latest updates between issues.