UNDER THE SKIN: LOLA FORMULA 5000 – LIFE BEGINS AT FIFTY

It’s 50 years since Formula 5000 started around the world and one of the most evocative cars of that era remains Lola’s glorious T330

By PHIL BRANAGAN

OFTEN IN the history of motor racing, one can say that a car changed a category.

Various Porsches have done that; the 907, the 956/962, even the just-retired 919. Audi’s Quattro and its diesel-powered Le Mans winners. Roger Penske’s pushrod Mercedes-Benz IndyCar that won the Indy 500 in 1994.

Lola changed Formula 5000 in the 1970s. It is 50 years ago that the category first appeared and for a while, a number of makes fought it out for superiority – including Lola. While Elfin, Frank Matich and Graham McRae were refining their own cars for local competition

Lola was very much in the business of selling racing cars to customers, so at the dawn of the F5000 era, it was well-placed. In 1968 it offered the T140, which found a market in the USA, followed by the T142. By 1970 it was clear that the existing blueprint of front radiator cars with add-on wings was not going to suffice – Lotus’s 72 was starting to make those cars look redundant in F1, so it was only a matter of time before that technology trickled down to F5000.

Frank Gardner had sorted out John Surtees’s T190 F5000, which Mike Hailwood raced, and when Lola wanted to build a car specific to the new Formula, the laconic Aussie something lighter and better. Lola’s T240 chassis – which was meant for Formula 2 and Atlantics – got his mind going.

In the most American thing in the world, out went the four-banger and in went a small block Chevy V8.

Gardner himself debuted the new car at Oulton Park in August 1971, and once he won the British title it quickly found a market. But just as quickly it became clear that the car was tricky to drive on the limit and of the 18 cars built, six were written off in crashes.

The Front Bodywork of the Lola T330

Then came the 330. Against strong opposition, particularly from the likes of Graham McRae and Chevron, this is the car that changed F5000, with 25 built during 1973 and ’74.

The 330 was a far better car. Just as he had with the Surtees Gardner looked for a lower and longer tub, to give the car a lower Centre of Gravity and additional stiffness. So successful was the car that it changed the way F5000s were looked upon; suddenly, you did not have to be a Matich or a McRae and have the capability to develop your own car or have Chevron do it for you, to be competitive.

The good news was, if you could drive well enough, you could buy a Lola and race at the top level. The flipside of that was; among the opposition and in similar cars were names like Andretti, Unser and Redman…

Which is where this car comes in. The T330 we looked at is chassis number HU8; the ‘HU’ means that it was built at Lola’s Huntingdon factory, where it had moved in late 1970. This car was sold, via American Lola agent Carl Haas, to Jim Hall in early 1973. Hall’s team raced the car with Brian Redman at the wheel, and in 1975, Kenny Smith acquired the car and brought it to New Zealand.

Smith raced it on both sides of the Tasman until 1977, at which point John Blanden bought the car, and it was raced by Rob Butcher and Chris Milton. Bib Stillwell bought the car in the 1980s and in 1993, Noel and Andrew Robson bought it – and they still have it.

“Bib was the last owner before us,” said Andrew Robson, “and he had three cars for sale are the time, this one and two Brabhams. We had always wanted a Formula 5000, and once we got involved in Historic racing, there was a strong attraction to these cars. I watched them when I was a kid; Dad was racing other cars, like the MG.

“It was in very good condition. Bib really looked after his cars. It was in his colours, green and yellow, so we changed it back.

“Haas had two cars; HU8 and KU14. This car was slightly modified by Jim Hall and Redman drove both at the start of the season, and he had to choose between them; the ‘Broadley’ car or the ‘Hall’ car. They had slightly different radiators and a few other mods.

“The rear suspension is still 330. The 332s had a parallel link at the rear.”

One thing about a series that produced so many different cars is how owners mixed and matched their components, and the Robson Lola is no exception. In F5000 eligible engines came from AMC, Buick, Chrysler and Dodge, Ford, Repco/Holden, Mercury, Oldsmobile, Plymouth, Pontiac and even Jeep, but by far the dominant engine, in terms of both its widespread use and results, was the Chevrolet.

The Chevy 101 block

On the Robson car, on top of a Chevy 101 block sit Brodix aluminium heads, with a 23-degree angle between the valves, which was common for the day but which has been modified by some users of the years. Some highly-developed Chevs had run 18 degrees, which will be familiar to early-2000s V8 Supercar fans. Now the rules limit modifications to 23 degrees, with a maximum port height of 63mm and width of 33.02mm.

On top of that things get no less complicated. Variants of the Chevy engines used carburettors or fuel injection back in the day, with many listing ‘Lucas’ as their brand of injectors. But for this application, Lucas doesn’t make complete injection systems, just metering units. To complete the mechanical injection the Robson car has a Mackay manifold and injectors by Kinsler in Troy, Michigan, which supplies all manner of fuel system items across a wide range of motorsport applications.

All that produces around 530hp and just over 400lb/ft of torque.

“The good thing about a 5000 is that you can buy parts readily,” Robson said. “There is nothing fancy in this one; there are some that are unbelievably powerful, some of them pushing 600 horsepower or beyond.

“The internals are free. There are some guys out there probably running titanium bits, and wanting to put NASCAR heads on them, and that is getting away from the concept a bit.”

All that means that for most Australian and NZ circuits, the car would top out around 275kmh. At some of the faster tracks back in the day – like Road America – some of the cars got over 300kmh.

Engine life is around 3500km, with only adjustments to tappets and oil changes between races. That translates to around 10 race meetings; even in a busy season, that might be three or four years, given that the Robsons have a Ralt RT4 and a Brabham Formula 2 car sitting in the garage as well.

Behind the engine sits a standard AP triple plate Clutch with heavy duty springs, and the near-ubiquitous Hewland DG300 gearbox. The engine is semi-stressed, bolted to a subframe that is bolted to the tub.

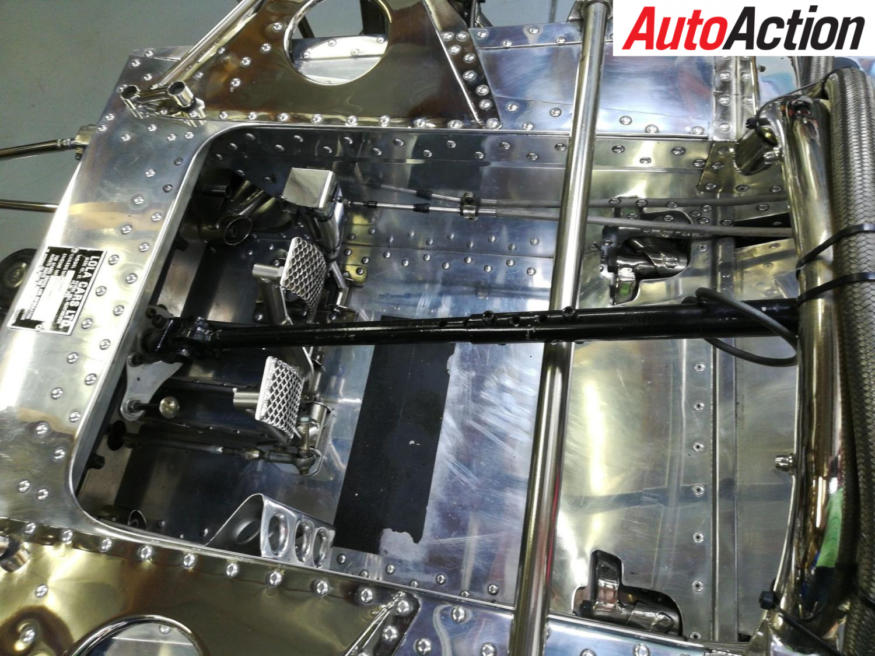

The tub itself is longer and lower than the one in the T300, and which has prompted Lola evergreen Kenny Smith, who races his own T332 in New Zealand, to compare it to sitting in a big armchair… that does 175mph.

One thing you do not want to do with a Formula 5000, or any racing car for that matter, is have a crash and two years ago Robson had a big one at Sandown (what is it about that track and Lolas?) Once the car was returned to the workshop one thing Noel Robson insisted on was new uprights and suspension on all the corners, and then they needed a new tub.

The one that the car has now is based on a 332.

“You have to build them,” Andrew said. “This tub was hand-built in Melbourne by Brian and Gavin Sala, and Jay Bondini folded and punched the skins. They have the original drawing.

“Things like wishbones, fabricators just make them. The corners are all brand new. The bearings are standard Timkens. The wishbones have to be hand-done, and they cost around $1500 each.

“The brakes are a bit hard to get, they are APs and cost about $450 to bring in, or $250 if you can get them locally. You have to make slight modifications depending on which cars they were on.”

Says Noel, “The brakes are as the car came, as Bib had them for six years before we got the car. They are fitted with Porterfield brake pads; they seem to work well and they last, though there are softer ones available, and they tear up the rotors a bit.”

Going inside, Koni dampers sit inside the single set of springs, and are rebuildable. The tyres are cross-plies, Avon A11s, and they last up to three meetings for $2500.

The attraction of Formula 5000s is obvious. If the swoopy Lola looked like something out of a yet-to-be-made Sci-Fi movie in 1973, it is still a good looker in 2018.

“It’s exciting,” said Noel.

“Andrew is the driver; but just for me, the noise, the look of the car, they are a special thing. It’s not exciting but not for Andrew; he has to be too busy saving his own life.”

Counters Andrew; “It’s not so great when you punch it into a wall. At Sandown, we had some sort of tyre failure. I went onto the back straight, before the kink, and Paul Zazarin was in front of me. All of a sudden he lost power and I dodged out to miss him, and I thought I was clear, then all hell broke loose.

“From the video from the car behind us, it seemed like I was clear and it was the tyre. It was like I had hit him with the right wheel, but I hadn’t, and the car just turned in.”

And he is clear that the car’s near-Supercar power and 1973 chassis technology demands a certain touch.

“I have always driven this car with care, let’s say. I have been very successful; we had three lap records and held them for a long time. But you have to respect them; you have to be conservative with the Lola, whereas the Ralt goes better the harder you push it. Some of the young blokes now they seem to push pretty hard, but you always had to give the cars respect.”

Next week’s Phillip Island Festival of Motorsport will be the ideal place to see the cars in action. About a dozen Aussie-based F5000s will face off against about 10 from New Zealand at Phillip Island.

“The Phillip Island meeting attracts well over 400 entries,” says Andrew.

“People who looked at these cars back in their day, they still want to come out and see them today. “

A third-generation Robson, Andrew’s son Dean, has raced Formula Ford in Historic racing but has “dropped out to race pushbikes” his father says.

In the meantime Formula 5000’s legacy is in good hands. Half a century after they first appeared, the Wow Factor is still there – to the point that there have been two separate projects in the last few years to revive the enthusiasm many fans have for big, loud open-wheeler racing cars.

What happens when those cars hit the track will be interesting. But for now, the original 5000s still make the ground shake, and the hairs on the back of the neck stand up…

THE SUCCESSOR – THE LOLA T332

The successor, the Lola T332

IF THE T330 changed the face of Formula 5000 its successor knocked it out of the park.

The T332 was a refined version of the T330 and described by some as nearly the perfect racing car. Various teams and drivers around the world used the newer car to win the UK and US series in 1974, the Tasman and US series in 1975 and the US series in 1976.

In all, 36 T332s were built, and many are still racing around the world.

At various stages, Lola was the biggest manufacturer of racing cars in the world, but if many of its cars survive, the company itself did not. In spite of advice to the contrary founder Eric Broadley still harboured a desire to win in GP racing, and in 1997 a Mastercard-backed Lola team came to Melbourne for the opening GP of the season.

It was a disaster and the company never recovered. Irish businessman Martin Birrane acquired the company a year later and guided it to a 50th anniversary in 2008. But four years later the administrators were brought in.

In more than 50 years Lola built 240 different cars, for Formula Junior to F1, and nearly 4000 cars wear the four-letter nameplate.

TECH SPECS

Lola T330/HU8

Built January 1973

Engine

Chevrolet ‘101’ block

Capacity 4994cc

Cylinder Heads Brodix aluminium

Fuel Injection Kinsler/Lucas mechanical

Power Approx. 530hp at 7000rpm

Torque Approx. 400ft/lbs

Chassis

Alloy and Steel monocoque with twin bulkheads

Bonded and riveted construction incorporating twin fuel cells (114 litre capacity)

Semi-stressed engine

Bodywork

Two-piece colour-impregnated fibreglass reinforced plastic by Specialised Mouldings

Suspension

F Tubular Uneven Wishbones

R Upper: Trailing Links and Radius rods

Lower: Tubular Wishbone

Dimensions

Length 4826mm

Wheelbase 2591mm

Width 2057mm

Height (roll bar) 940mm

Track F/R 1625mm

Gearbox

Hewland DG300 five-speed plus reverse

Clutch

AP 7.5 inch, triple plate

Wheels

Lola magnesium alloy

F 13 x 10.5 inches

R 15 x 17 inches

Tyres Avon A11 cross-ply

Weight 665kg/1375

Article originally published in Issue 1731 of Auto Action.

For our latest Under The Skin feature pick up the current issue of Auto Action Magazine, on sale now. In the meantime follow us on social media Facebook, Twitter, Instagram or sign up for our weekly email newsletter for all the latest updates.