UNDER THE SKIN: TOURING CAR MASTERS FORD MUSTANG – THE FRENCH CONNECTION

The French Connection – Rusty French’s Touring Car Masters Ford Mustang

Even in a large collection of all-black racing cars Rusty French’s Ford Mustang Touring Car Masters racer stands out. Nothing has been spared on making this one of the category’s most eye-catching cars

Rusty French racing his Ford Mustang in Darwin

EVERYBODY has a favourite car from their younger days. OK; maybe some people have more than one…

For me it is the Ford Mustang. There was just something about the original Pony car, which in the mid-1960s not only gave Ford a boost, it started a whole new genre of road cars.

Sure, underneath the swoopy exterior they were really a Falcon underneath (and some of them were six-cylinders, to boot) and the ones that made it to Australia (Ford assembled right-hand-drive versions locally) were not that so uncommon on the roads that I don’t clearly remember ever seeing one.

But some of them found their way onto the racetrack and in the early 1970s the lines of the car, its stance and presence, and its motorsport pedigree – yes, Mr Moffat, I am looking at you – made it stand out.

Rusty French feels the same way about many cars – in particular, Fords and Porsches. And the long-time racer, car owner, Porsche and Ford enthusiast and for the last four years, as co-owner of Prodrive Racing Australia, has a couple of ‘Stangs, and this one is a cracker.

There is no lack of enthusiasm for racing cars from French. Even into his 70s – and five decades years after he started racing – he remains as passionate as ever, and his car collection shows no sign of getting smaller any time soon.

Rusty French is also a co-owner of Prodrive Racing Australia

One might expect that, as the owner of a four-car strong Supercars team (more, if you count the Super2 entries), building a Touring Car Masters car would be a relatively straightforward mission, as simple as starting a new project at the team’s Campbellfield HQ. Not so.

French was not keen on interfering with the team’s day-to-day priorities so it was decided to sub-contract the build out.

‘Out’ turned out to be the Adelaide workshops of Supashock, and long-time ally Oscar Fiorinotto.

“Rusty was prepared to step out of the typical ‘TCM Box’, if you want to put it that way,” he told Auto Action.

“He wanted to come up with a vehicle that not only set the standard aesthetically, but a car with the best technology available within the rules, and a car that was a pleasure to drive. That is what we wanted to create; anyone who sees the car, or drives it, says it is not a typical TCM car. It is nimble.”

The project started with a bodyshell, which was sent west to get things started.

“He brought me a shell and even when they were new, back in the day, they were not made to a very high tolerance,” says Fiorinotto.

“We built a jig and squared the shell up, and then I said to Rusty, ‘what do you want me to do? We can used this shell but to be honest, it is not that great’. There were issues with it; corrosion, rust, that sort of thing.

“The car had seen its day. It was straight but we made the decision to start from scratch.”

Rusty French’s Mustang was built from the ground up, same as a Supercar

One of the interesting things about a Mustang – or a Chevy Camaro or Pontiac Firebird, or other American classics – is that you don’t need to start with an old one. You could – but you can get a brand-new reproduction of a body shell, and every panel. That is what happened in this case.

“We built the shell ground up, panel-built, the same as a Supercar,” says Fiorinotto.

“We built the jig and brought in every panel from the USA, brand-new. That way we could be precise; across the 4.5 metre vehicle we could work to a tolerance of half a millimetre.

“That took some time. In relative terms it was a quick build; some of the TCM cars have taken up to two years. We built this one in six months.”

That does not mean that anything was rushed. With a lot of engineering capability at hand, it came as no surprise that the design of the car was done digitally first, before anything was cut and welded together.

“The whole car was computer modelled, every single component,” Fiorinotto explains.

Inside Rusty French’s Touring Car Masters For Mustang

“We went as far as we could go with the roll cage, we explored the rules to the maximum so we could maximise torsional rigidity. We were able to build the vehicle and from our testing, we derived a lineal torsional stiffness from front to rear. That was difficult because the TCM rules state that you cannot just go adding bars to the front of the car. That was key element.

“We built it from a combination of T45 and 4130 chrome moly – a percentage of each. The CAMS regulations are such that we had to optimise the wall thickness across the whole cage. They require a heavy wall roll-over bar, and that often means that the torsional stiffness is towards the rear.”

As one might expect from an engineer whose main business these days is Supashock – and you can find them in road cars nowadays – the suspension of the car was subject to a lot of attention. It is also subject to a lot of limitations.

“There are limited freedoms with the suspension. You still have to use standard suspension arms, so the big thing is, how you can improve the stiffness of the suspension. That is the key, even moreso than the geometry. We had to stick with certain components.

“Optimising roll stiffness was relatively straightforward because we had such a good chassis. We did not have to go with exorbitant roll bars.

“We designed the suspension ourselves. Obviously the arms are reinforced, and we maximised the geometry. It has double wishbones at the front, same as the standard Mustang, and a live axle at the rear.

“That was a challenge. We designed a three-link system, as opposed to a four-link. That gives you extra adjustability, in regards to pitch or anti-squat geometry.

“It has full roll-centre adjustment, with a Watts Link, with out own leaf spring system. We designed our own leaf springs and King Springs made them for us.”

One of the car’s initial challenges was with the steering

One of the car’s initial challenges was with the steering, which was over-sensitive, but changes made the car much more drivable over the last season.

The diff and axles were supplied by Race Products in Queensland, which has vast experience in a wide range of applications, and which also supplied the axles. The ubiquitous nine-inch diff is used as the basis of all the RWD cars in the TCM. The hubs were supplied by Dick Savy of Savy Motorsport, to a Supashock design.

One of the limiting factors in the category is getting the cars stopped. With a 15-inch wheel room inside the rim is limited, and disc rotors are limited to 305mm in diameter and 35mm in width. No cross drilling is permitted, but grooving is. Four piston callipers and two pads are mandatory.

“Brakes are a Supashock design,” says Fiorinotto.

“The strap is the same as a Supercar, in the disc mounting system, to allow disc modulation. Because you have such a small disc rotor modulation is a key component. It’s only 305mm but the braking of the car is quite strong. It runs Brembo calipers on top of AP rotors, with the rest Supashock.”

The cooling of the brakes is limited, with ducts limited to 300mm by 100mm. No form of cooling other than air is allowed.

Running 1960s technology – even if the parts are brand new – has its challenges. One is that many of the items that make today’s Supercars look bulletproof compared to the cars of the past is their engine management and fuel systems. Short of inadvertently leaving the odd rag or blocker in an inlet, cars do not often fail to start races in the pro categories these days.

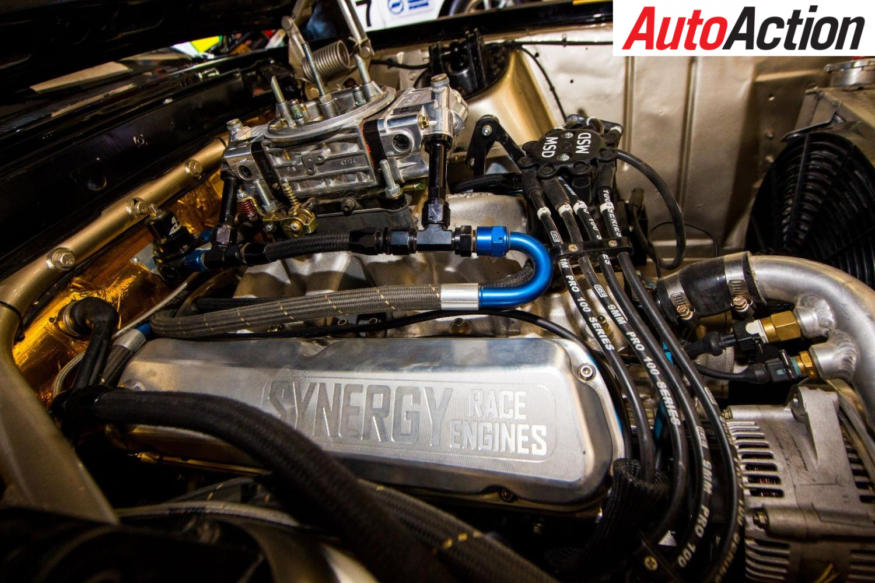

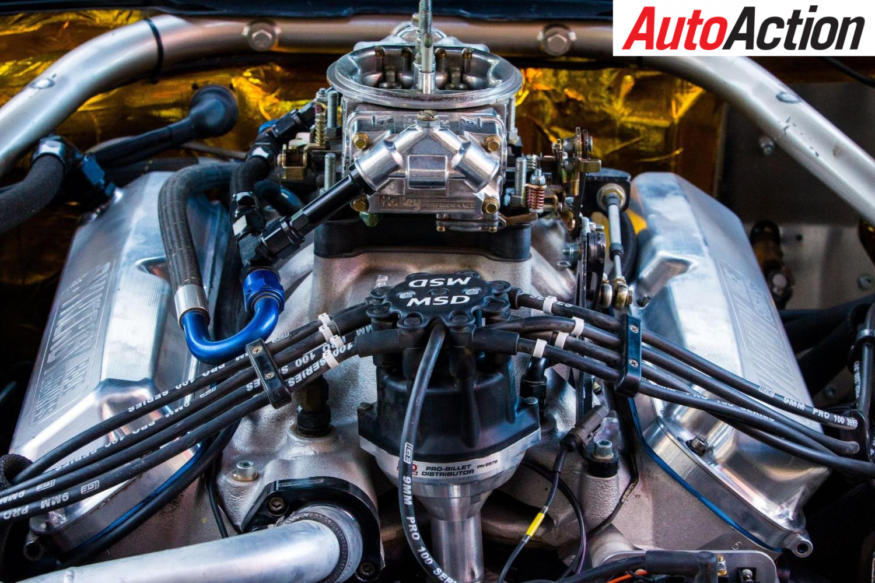

Under the hood of Rusty French’s Ford Mustang

That make getting the fuel system right something of a challenge.

“With the carburettor, the fuel can get hot very quickly,” says Fioinotto. “We worked very hard to prevent any vaporisation, to control the temperatures from the tank to the carburettor and return. That was key; many cars will not start on the dummy grid because of vaporisation.

“The fuel system was designed by us. It has an FIA certified tank from Italy, from M.E.RIN, a company that supplies many of the teams in the World Rally Championship. The tank is specifically designed for this car. We optimised the weight distribution, and we designed it to reduce fuel surge.”

At the other end of the fuel system is the heart of any TCM car, its engine – and in this case, ‘what is it?’ gets a one-word answer. Any Ford fan knows what ‘Windsor’ means (it’s actually a town in Ontario Canada, a few kilometres from the US border, but you take my drift…).

So the French car has a Windsor. Except, it’s not. The original Windsor was produced for 40 years, and the last Ford road cars to run one were Aussie Falcons and Fairlanes, 15 years ago.

But now, everything old is new-ish. French’s engines, and some for the other Ford racers in the TCM, were built in Melbourne by Steve Makarios of Synergy Engines.

“When you repeat it over and over you kind of get the hang of it,” he said.

“You could run a 302 Boss, with a Windsor bottom end and like a Cleveland top. But when we discuss the pros and cons of it, it always comes back to a Windsor. They make a lot more torque and they are not rev-limited.”

Like the bodyshell and panels, one does not need to go back in time to get an older Windsor engine when new ones can just be one click (and a whole lot of PayPal) away.

The car runs a Ford Windsor built by Synergy Engines

“This is a Dart aftermarket block, with their heads,” says Makarios.

“They are all new, and all strong. It’s exactly the same as the original Windsor, the heads are homolgated for that motor – but

I think that there is a new set of heads that is also eligible for that motor.

“You are limited to standard cubic inches and your fuel, and to 7500prm. You have to run a single four-barrel carburettor, but apart from that, you can change a few things.

“The engines are very similar. When I built the motors for John Bowe and Steve Johnson they had to be a bit different, because they win a lot they get penalised on their RPM. So I had to build engines that made their power lower in the rev range. At some point JB was down about 1000rpm when he was in the Mustang. He was not winning but he was still competitive.

“The ignition is MSD, everyone runs that and it is sealed with the rev limit. It’s a proven package, the engines need a freshen up once a season. We had one incident, the owner of one car went a season and a half and it had a problem with the valves. He was aware of the risks, and he ended up paying for it.”

TCM rules allow are variety of gearboxes to be used, and the Andrews A431 four-speeder is popular. Tried and proven in NASCAR competition and unit is available with a selection of ratios, which in this case, were chosen by Fiorinotto.

The wheels are 15 inches in diameter, and eight inches wide, with 245 (front) and 275 (rear) section Hoosier tyres.

One of the areas where the French car is different to many is in the cockpit. This is one of the car’s priorities; it had to look right. Most of the components are brand-name items from Racer Industries but Fiorinotto did not stop there.

“We took a lot of care with the aesthetics,” he says. “Everything was optimised for weight; the car came in significantly under the weight limit; by 80kg, if I remember correctly. We wanted the car to be beautiful and it is. Last year it won the best-presented TCM car.

“We made the dash. Aesthetically it was important to get the dashboard right and it is all Alcantara, and so is the seat. We had that done especially.”

The interior of Rusty French’s Ford Mustang

Like many of French’s cars – two Porsche 935s, two De Tomaso Panteras – the car has a ‘twin’. It was always the intention that along with a Mustang in the TCM there would be a more ‘traditional’ version, to race in Group N. That has been built, also by Fionotto, and the standard of its presentation is just as impressive.

And the big question; what does a car like this cost to put on the track?

The engine is straightforward enough. Says Makarios, “Rusty wanted the best of everything in his engine. Something similar to his, with an open chequebook, would be anywhere between $60 to $70K. With something like the Stevie Johnson, with some heavy artillery items in there, it might be closer to $50,000.”

But it is much more difficult – and it would probably be rude to press for an exact number – to get a total out of Fiorinotto.

“It was not cheap,” he says, “but it was not that expensive either, cheaper than some of the numbers that I have heard going around. I would be keen to do more but I did this as a favour to Rusty.”

Having built one and only one Touring Car Masters racer, and seen it race competitively, it may well be that there may be another Fiorinotto car on the track some time in the future.

“If someone came along and wanted to build a car to that level, and they were dead-set keen on it working properly, I would be interested,” he says.

Like many of the leading TCM racers the standard of presentation of the French Mustang is second to none – and it sounds just right too…

Some time soon someone, surely, will put their hand up for another one of these.

Rusty French – The Man In Black

THE MAN IN BLACK

RUSTY French loves his Mustang – like he does all of his racers – but it was not love at first sight.

At first, the ‘Stang did not want to go around corners.

“We did some work to get the roll centre right, the pivot point was out a bit,” he said. “We got Derek van Zelm to shorten it and it was much better

“I think that the car was underweight and that was fine, we added weight to it. It understeered, and one of the reasons was that we had a Trutrac diff in it. That tended to be a bit more towards a ‘locker’, so that you would get off the power and get into a turn and it kept pushing you forward.

“So we went to a limited slip and that is turning in quite well now. That has also changed the handling well as well.’

“But, mechanically it has been fine. The engine is good and the gearboxes, from Andrews in America, are very good. I think that it has just what we wanted, but if you jump out of it and into something newer – like the Kumho car we just bought – you think to yourself, ‘why do we play around with these old things?’ We get them as nice as we can but they are still an old car!”

TECH SPECS

Body: 1969 Ford Mustang Fastback

Length: 4762mm

Width: 1821mm

Height: 1283mm

Wheelbase: 2743mm

Weight: 1530kg (minimum)

Engine

Synergy Race Engines

351 cubic inch pushrod Ford ‘Windsor’ V8

Block: Dart, 9.503 inch deck height

Bore/Stroke: 4.000inch/3.500inch

Edelbrock intake manifold,

Holley four-barrel carburettor

Gearbox: Andrews A431

Four-speed, ‘dog’ gears

Fuel tank: M.E.Rin, custom design

Suspension: F Supashock dampers with King Springs

R Leaf Springs by King Springs to Supashock design

By PHIL BRANAGAN

Article originally published in Issue 1718 of Auto Action.

For our latest Under The Skin feature pick up the current issue of Auto Action Magazine, on sale now. In the meantime follow us on social media Facebook, Twitter, Instagram or sign up for our weekly email newsletter for all the latest updates.