UNDER THE SKIN: ACDELCO TOP DOORSLAMER – THE BLUNT OBJECT

The ACDelco Top DoorSlammer

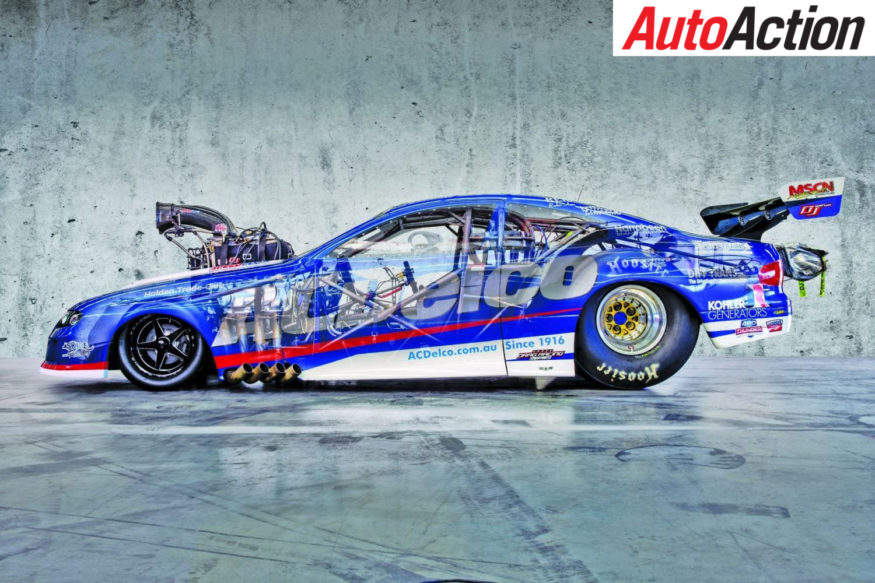

Doorslammers have become one of Drag Racing’s biggest attractions, for good reason. There is a lot to see – and Maurice Fabietti’s AC Delco Holden Monaro is one of the Slamminest ‘Slammers in the sport

UNLESS YOU have been hiding under a rock for the last 20 years – and it would have to be a big rock – you will know what a Doorslammer is.

By PHIL BRANAGAN

Under the skin of the AC Delco Top Doorslammer

The bracket has emerged as one of the fan favourites across the country and the wide variety of cars offers something for nearly everyone.

One of the most watched cars in the category is Maurice Fabietti’s AC Delco Holden Monaro. The smooth coupe has been one of the cars to beat since it first appeared, and represents one of the best-presented race cars in Drag Racing.

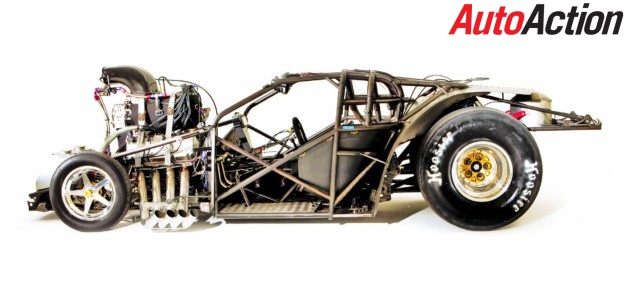

Like so many Doorslammers – or Pro Modifieds – life for the Monaro started in the World Headquarters of Doorslammers. In the eastern suburbs of Melbourne, the workshops of Anderson Race Cars has been Australia’s premier drag racing chassis builder for the past 27 years, having built many race and championship winning, and record-setting Top Doorslammers.

The ACDelco Top Doorslammer in action

Murray Anderson first rose to prominence in the early 1990s having built Raf Pironti’s AA/Gas Torana hatchback, and George Clasby’s record-setting two-door Skyline, one of the country’s first 200mph Doorslammers.

Since then Anderson has designed and built many popular Doorslammer body styles, including the ’53 Studebaker and ’67 Camaro, of which there are now hundreds of examples around the world (he sold the moulds to a US composites company for the US market).

First of the Americans to win in an Anderson car was Scotty Cannon, whose Studebaker won the IHRA Pro Mod championship in its first season of competition in the USA. Other American drivers in Anderson cars include Jim Oddy/Fred Hahn in the NHRA Pro Mod championship-winning C6 Corvette; Al Billes’s record-setting Pro Mod Studebaker; and Jay Payne’s Chev Camaro.

“Murray Anderson built it about eight years ago,” Fabietti told Auto Action.

“It was purpose-built as a Top Doorslammer Monaro, prior to that I had a Terry’s Diffs and Chassis Pontiac Trans Am and Murray had done some upgrades on that. We re-bodied it into a Monaro and we had Murray do the front and rear ends on that.

“When I could afford it, I sold that car off and got Murray to build a purpose-built car to run in Top Doorslammer. Murray built the rolling chassis and we finished it off in our shop; we mounted the body, did the pedals and seat, the glass and the tin work, we finished it.

“The full Anderson car has a lot of advantages; the engine is in exactly the right place; it weighs the right amount. It is super strong in the back of the car, and that is crucial. The rear end is what steers these cars down the track. The front end is just there to stop the thing from dragging on the ground!

“The rear is very stiff, it has to be to transmit 3500 horsepower through 17.5-inch slicks down onto the ground. Where the back end wants to go, that is where the car goes.”

That is where Anderson cars show their strengths. Anderson’s four-link rear end has become the standard for cars across the world, for good reason.

“Some of the early Anderson cars – Victor’s and the Scotty Cannon car – were built with a swing-arm,” said Fabietti. “That is, two fixed points on the diff and one hinged point at the front, where it connects to the chassis. That works pretty good but there is not a lot of adjustment.

“With the four-link, there are two attachment points on the diff and two attachment points on the chassis, on either side. It is very adjustable; you can adjust the top and bottom arms, you can adjust for traction at different tracks. If there is a lot of traction you do not need the tyres to bite in as hard. With poor traction, you need more bite. A four-link rear end is a lot more adjustable.

The rear end of the Doorslammer

“They make 3500 horsepower and the rear end – suspension, shocks – is very critical. You need that fine line between spinning the rears and tyre shake. We run JRI Shocks out of the USA, fantastic shock with multiple adjustments for compression and rebound. Different settings for different tracks. The springs are pretty much set; we just adjust the dampening between track.”

Starting at the back, one of the key areas is the diff and – would you know it – the technology would be familiar to people right across the sport.

“The diff is a copy of a Ford 9-inch diff; that is how it started but we actually use 10-inch gears in it,” Fabietti explains.

“It’s a 9-inch on steroids! It is made by Tom’s Diffs in America, the housing itself is made from a billet and it has a 40-spline spool with a 10-inch gear-set. It has a 4.57 ratio. These things are very hard on ring and pinions. It started with a 9-inch, they stepped that up to 9.5 and now everyone has 10-inch.

“With a 9.5, we would only be getting a meeting or two out of them. With a 10-inch, with the right clearances and the right oil, we can get 30 to 40 runs out of a gear-set. At $1500 for a ring and pinion, you have to try to make the things last.

“The ratio is in, at the end of the day with your ratio and tyre size you want to cross the line at roughly 10,000-10,300rpm. So 4.56 is the number we use. If you get a good clutch lockup, with that tyre size, at 250 miles and hour that gives you just on 10,000rpm at the lights.”

From there, the parts list features some of the big brand names in the sport, starting with a three-speed Lenco gearbox.

“The Lenco is a fantastic transmission. Super strong, we have different gearboxes with different ratios, and we change for different track conditions. If the track is not that great, we will calm it down in first gear with the gearbox ratio. If the track is super aggressive we will put a very aggressive first gear in it and hit the tyre a lot harder. It is all about not getting tyre shake.

We can change the boxes in about 10 minutes.

Tyre shake is the biggest killer in Top Doorslammer

“Tyre shake is the biggest killer in Top Doorslammer. That is what makes or brakes you getting down the track. Once you can get a handle on what it takes to get down the track without tyre shake, the rest is pretty simple!”

The gearbox is connected to a Molinari clutch and the art of setting that up, as always, seems to be about 50 percent science, 50 percent art and 25 percent faulty mathematics…

“The clutch is all about getting the right amount,” Fabietti explains, “not enough to get it shaking but enough to lock up to get a good speed and ET out of it. We use a lockup clutch; we slide the clutch in first gear, with only three levers operating; in second gear, it allows all six levers to come in, and the clutch locks up. The bearing comes back and lets the other three levers to work, and that applies more load to the tyres.

“It is full titanium. This clutch is five years old, it has wearing components but the clutch and flywheel are parts that last a long time. You have bolt-on wear plates; they are a disposable item. Every meeting you pull the clutch out of it and put three reground discs and two floaters in it. It had sintered iron discs and steel floaters.

“You have a multitude of adjustments, with six springs, then the six levers, and they have holes in them in which add or remove weights . The levers moves out centrifugally and that gives the clutch more force.”

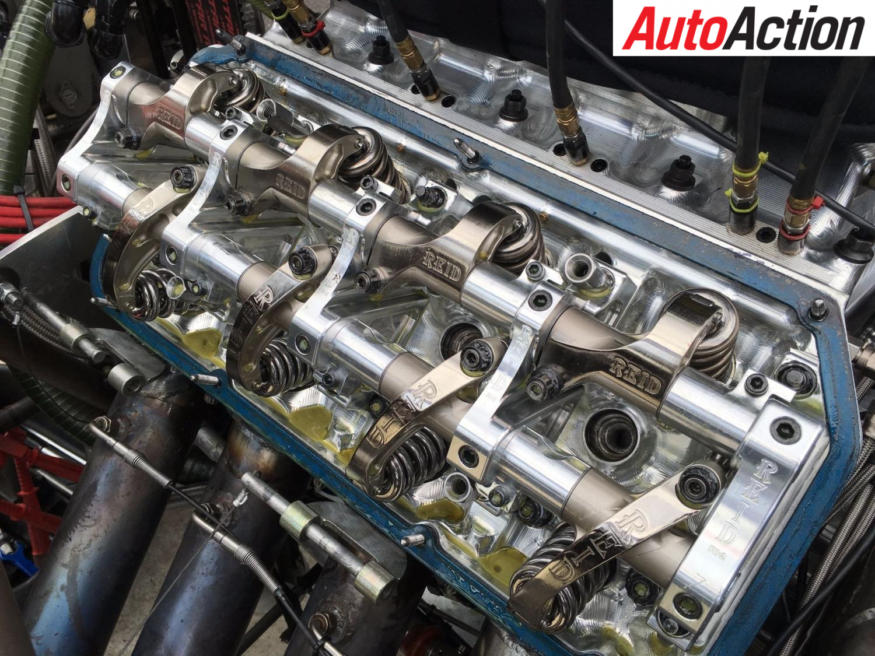

A look inside the engine

The brand names continue in the engine department, and one of the more tunable items is the MSD 44 Pro Mag Ignition.

“The MSD Power Grid gives you an adjustable curve,” said Fabietti. “You can pull timing in and out of it. You join the dots, you just plot a series of dots and the ignition system will follow that trace.

“The unique thing is, anything we run is not allowed to be reactive. You cannot have any forms of traction control, everything has to be pre-set in the pits. It is not allowed to sense tyre slip and pull some timing out of it. It has to be done by the driver or pre-set in the pits.

“You have look at the track before the run, put the tune-up in the car and hopefully, it will get down the track!”

And ‘connected’ to the ‘mag’ is a big lump of horsepower; the Brad Anderson alloy block, fitted with Noonan Race Engineering alloy heads, manifold and valve covers, all made from billet aluminium.

“The cost, from hat to pan motor, is about $140,000,” said Fabietti.

“It is very high maintenance and a very high turnover of parts. You get 16 to 20 runs on a set of billet aluminium conrods.

About 70 runs on crankshafts and valves. The thing is, these engines are a copy of a Chrysler 426 hemi, designed in the late-1950s, early ’60s. We still use that engine as a base. The original was made to make, maybe, 500hp and turn to 5000rpm. We make 3500hp at 10,500rpm! It is a good package and good to work on but you need to catch everything before it becomes a problem.

“And there is no cooling at all. The methanol we use acts as a coolant, as it goes through the motor and the heads and cools the engines.

Maybe the most important part of the whole package is the car’s supercharger.

Maybe the most important part of the whole package is the car’s supercharger.

“In Top Fuel and Funny Car they make their horsepower with their fuel,” Fabietti explains.

“We can’t run nitromethane so we make our horsepower with compression and boost.

“It is a PSI screw supercharger. The Rootes originated on a GM truck engine but these are purpose-built for Drag Racing. It compresses the air as it is twisting. To make it work you need to turn them faster than the engine. The class limit is 108 percent and we run our at 106 percent. So if the engine is turning at 10,000rpm, the blower is turning at nearly 21,000rpm.

“We have 50 pounds of boost, 10:1 compression ratio, a hell of a lot of bang for your buck. We use methanol, wood alcohol, a no-name brand. It’s as cheap as chips, a buck a litre, and we burn 20 litres in a pass.”

And then there is data logging. For road racers accustomed to watching everything that can be driven by data, the Racetrack data logger might seem basic, but it is that was for good reason. Cost is a big factor.

“It is only allowed to read what is happening,” said Fabietti. “The only function it is allowed to drive is the shift light. It gives you about 45 channels of information; three RPMs, throttle position, temperatures, pressures, shock position, positive and negative G-forces… a variety of things. You analyse it after a run and adjust things from there.”

The car goes through a $1200 pair of Hoosier tyres every 20 runs, and the fronts last… well, a long time. Development never stops on the car’s major components.

“You will always find weakness and you need to modify things. You are constantly developing things and it never ends.

Nothing is super-delicate, but when we come back from a pass, the five guys working on the car have their set routines; one is straight underneath the car and check every nut and bolt in the rear suspension. Someone’s life is in that car and you have to stay on top of it all.

“There are a lot of vibrations and a lot of stress in these cars. You really need to watch everything.”

And the all-Australian look of the car is something that connects with the fans.

“People love it,” Fabietti said with a smile.

“People relate to a Holden. They drive to the tracks in a Holden. A lot of competitors have missed that; they go out there in their Studebakers, their Camaros, their ’57 Chevys, all those cars that might be fine in the USA. When was the last time you saw a ’67 Camaro down at the shops? Every third car will be a Commodore.

“That is what gives us such a fan following; it’s a Holden.”

HIRING THE GUN

MAURICE FABIETTI has raced for a long time but, after a lot of success, he made the tough decision to step out of the cockpit a few years ago.

Mark Belleri

Mark Belleri is now the man in charge of piloting the AC Delco Monaro and while Fabietti would like to be racing, he is content to take on a role out of the car.

“I drove for 35 years,” he said.

“Sooner or later you have to say, ‘Enough is enough’. I had a few crashes and put my wife through hell. It is not fair on her and my body has taken a bit of a beating. When the doctor said that I could end up in a wheelchair if I had another crash, I put it together that someone was telling me something smart.

“My reaction time was slipping and when these things get out of shape, they don’t give you any warning. It just gets out of shape and you are in the other lane. You could end up in a wall at 300kmh. It was time to hang the helmet up.

“It was a perfect opportunity. My good friends Lucky and Mark Belleri were competitors, but they had a big panel shop in Narrabeen and they didn’t have the time to do the whole series. I put a package together and we have a great team now.”

And the successes have come quickly, with Belleri making himself one of the men to beat in short order.

“Mark is a fantastic driver,” said Fabietti.

“He is young, his reactions are probably the best in the country. In two seasons together we were second last year and number one this year. We just have to keep it there now.”

Want to win the ride of a life time? AC Delco is offering you that opportunity.

After Auto Action’s latest Under the Skin feature? Pick up the current issue of the magazine, in stores now. Also follow us on social media Facebook, Twitter and Instagram for all the latest news.