UNDER THE SKIN: WEST WX10 – FROM SANDOWN TO LE MANS

Mark Lauke’s West WX10 in the Australian Protoype Series

The Australian Protoype Series had its debut meeting at Sandown earlier this month. One of the cars to watch in the series is the West, so Auto Action asked former champion Mark Lauke to show off his WX10

By HEATH MCALPINE

THE FIRST round of the Shannons Nationals hosted the inaugural meeting for the Australian Prototype Series, which has been born out of the Australian Sports Racer Series.

The series includes a variety of Le Mans style open top vehicles mixed in with Radicals and Ralph Firman Racing Formula 1000s, but primarily the open top sports racers dominate the class, with West representing the majority of these entries. Mark Laucke is a previous double champion of the Australian Sports Racer Series and heads the West brands attack on the series title.

Laucke was looking for something to race after his wife suggested he go racing, but struggled to find a car that matched the responsiveness of his previous love, which Karting. Finally, and completely by chance, Laucke and his wife saw the first West to land on Australian shores at an event and he couldn’t resist.

“I saw the very first West that had been imported into Australia at the local sporting car club when we were there for a dinner,” explained Laucke.

“My wife and I looked at it, we eyeballed it and we went up and kicked its tyres, spoke to the owner and I thought I better have a test drive of this because this was exactly what I was looking for.”

Apart from Karting, Laucke was an experience tarmac rally driver, but was a circuit racing novice. The West, however, proved to be an easy car for the novice to adapt to and the rest they say is history.

“I went for a drive at Mallala and in my first outing I got within two seconds of the lap record,” said Laucke.

“It’s just natural, easy to drive.”

“We worked out quickly that anybody like me, who had never driven in a circuit race before, could drive one of these things because there is not much gap between a professional driver and an amateur driver because the cars even that sort of stuff out for you. They make a bad driver look good.”

Behind the wheel of the West WX10

Laucke drives one of the latest Wests, a WX10, which is a considerable improvement over the previous model. Laucke’s example has been further developed since it was imported from the US, but also needed to be changed to conform to the Australian regulations.

“I upgraded to the current car, which was West’s prototype of the then latest model. West in America went broke, got bought out by a guy who was in many categories and is a multi-millionaire, who just got sick of funding it. Greg Steer of West Motorsport Australia bought what he wanted to off that company and then it was Aaron Steer from West’s task to develop the new model. I got the previous prototype and with Aaron, gradually started putting extra stuff on it, we had to modify it totally, and it had a turbo engine.

“When that car first came here, it couldn’t be used here, so Aaron did a lot of work to bring it up to Australian class and then we have been adapting ever since.

“Some of the equipment on it, for instance, was of quite high quality, but [with] no technician to maintain it, it was just horrible. In the end, after two years of trying, I have a simple gearshift system on it that actually works. It’s going now and I won my first race.”

Through the constant development in Australia, West in the US benefitted from the constant upgrades made by the Aussies. This made the Wests the cars to beat in America

“That car, whenever it went to America it always set the outright lap record,” continued Laucke.

“That’s how quick it was. It turned out that we were feeding information to West America, we told them what we were doing in Australia and this happened right from the start and kept the development of the cars going based on their Australian experience.”

Kawasaki ZX10R that powers the West WX10

A 2008 Kawasaki ZX10R motorcycle engine powers the West, though it is not the most powerful engine, it is the most reliable. With minimal tweaks an engine from a written-off bike can be installed into the West, which as Laucke explains, are very easy to acquire and very cost effective.

“They are so reliable,” he said.

“I’ve been racing these cars for eight years and I’ve only failed to finish a race once due to an engine problem. I normally get two years out of an engine and then I buy a second hand engine from a wrecked bike for nothing, get Aaron to check it out, change the mapping of the ECU to stop the humps and bumps to make it safe for a bike rider. We just straight-line the torque curves and power curves, allow the engine to do what it would like to do, raise the rev limit and then drive it.

“After two years, we never dare touch the head or valves, they’re always perfect and then we put new rings in it. If something goes wrong you change the big end bearing.

“The most I have spent on a total engine rebuild, which I didn’t need to do, cost $5000. That’s the strength of these cars.”

The same can be said for the Kawasaki gearbox, which is mated to the ZX10R engine. The gearbox is very easy to adapt the ratios to suit the various tracks that feature on the prototypes calendar and has been an improvement on what Laucke has used before.

The brake package on the West

The brake package is free in the Prototype Series, so Laucke uses high-quality PFC pads and calipers, while the rotors are as he describes them, ‘standard nothing-type rotors.’ After initially using Wilwood pads, Laucke found that they had good progression, but this was happening because they were flexing and these were replaced with higher quality PFC pads.

Kumho Tyres are the control tyre for the prototypes, but it has taken time for Laucke to adjust after using Avon tyres. Now, Laucke is getting the same speed from the Kumhos and is has found them much more user-friendly.

“We used to run Avons, we thought they were magnificent cross-ply, really grippy, long tyre life and their compounds were matched to the vehicles,” explained Laucke.

“The Kumhos are radials and took us a while to adapt to but now we’re doing similar lap times and the Kumhos are a lot more stable regarding temperature and tyre pressure. It’s a lot easier to manage them, but I know how to manage them being a Karter, so I have lost the advantage I used to have with the Kumhos.”

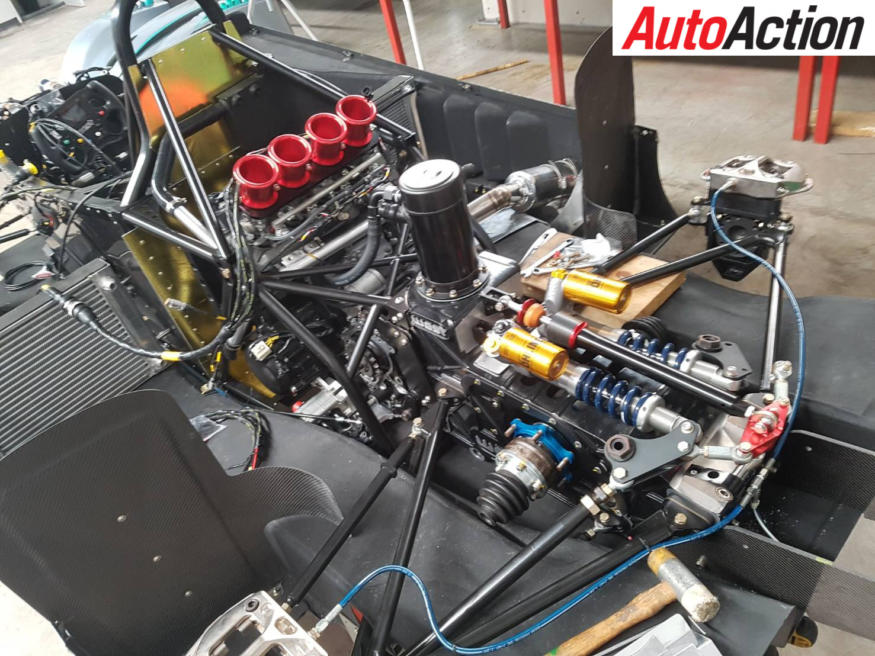

Rear suspension on the West WX10

The suspension is also an improvement over previous Wests, as improvements have been made to make the cars ride over the bumps, but Laucke’s car has a different set up to the other Wests, mainly due to the fact the car was the West developmental prototype.

‘The shock absorbers are inboard,” said Laucke. “All the suspensions are one-to-one ratio, so really simple and direct. It’s simple to calculate what you need to do and adjust everything.”

“My car is a bit different, originally it was delivered with the option of a third spring, so an in-board third spring to act as a roll controller. These things don’t roll, they have such a low centre of gravity and so light that they don’t roll. When I got it, I could see it had been all disconnected and had been experimented in using a pitch limited device, so when the car swaps under acceleration and dives under braking, you can actually see this thing move.

“I have put travel limiters on it so I can adjust the ride height is extremely important for these aero cars, 1-2mm makes a big difference, so we’re really fussy with ride height. We have to use every aspect of aero and handling, so that’s just what I’m learning to do now.”

Carbon Fibre body work on the West WX10

The bodywork is completely carbon fibre and is not designed for high downforce, but for easy flow through the air. The West features a flat bottom and a diffuser; the car cannot make adjustment to its front wing hence why the car has to flow through the air easily. The rear wing as Laucke explains isn’t there for downforce, “the wing at the back really doesn’t do much but it provides stability like wings on a dart.”

Laucke gave a rather scary example of how the aero works.

“Running at Phillip Island along the left hand side, I can aquaplane at 230km/h and the car stays straight because of the stabilising action of the wing and we have rear tunnels. That keeps the car straight all you do is lift off and wait for the grip to come back then accelerate again. There are beautifully stable in a straight line.”

What lies beneath the carbon fibre bodywork is a chrome-moly frame, which also features a cocoon to protect the driver.

“It’s the safest and most rigid,” said Laucke of the chrome-moly chassis. “It’s not the latest technology carbon fibre, but it’s a hell of a lot safer and better. It’s got two layers of carbon fibre, an inch and a half thick around the driver’s structure and around the driver’s legs. That’s inside all of the bodywork and that’s just a cocoon around the driver.

“It has steel upper and lower wishbones and rear sponson that mounts all the suspension and the differential is a bespoke item that is made by Aaron for these vehicles. It was originally in America a carbon fibre one not legal in Australia, so he has created a cast alloy one, which is better. It has the oil tank in there and a starter motor in there for reversing.”

The set up work on the West is fairly minimal, with Laucke finding that the car is adaptable to the various circuits and conditions.

“All you do is set the cambers to standard and never change them,” said Laucke. “You never touch the cambers because you don’t need to, you set the tow to be a little bit out, 2-3mm and never touch it again after that. If you had time and if it was wet you may give it a little bit of tow but you generally don’t need to. All you really change are your shock absorber settings and then if you’re getting fussy you might change your spring pre-load, so the cars are really adaptable.”

When it comes to disadvantages, there aren’t too many, but as shown by the first round at Sandown, the West does struggle in the wet mainly because of its lightness. However, the advantages outweigh the disadvantages in this case, and are the reason why Wests have become popular in the Prototype Series.

“The lightness of the car is its absolute strength,” said Laucke. “It makes it easier to drive because it’s more responsive due to less weight, so it’s better go round corners, better to brake, better to accelerate, because it’s light. It’s at a disadvantage in the wet because of that.”

The West WX10 racing at Phillip Island

The launch of the new Australian Prototype Series provided great racing over the opening weekend at Sandown, with Laucke finishing the round third and best of the West contingent in his WX10. The class is surprisingly cost effective, with a new West coming in at between $80,000-$100,000, a used one can be bought in Australia for around $50,000 or one imported from the ’States can be purchased for as low as $35,000. Considering the running costs are roughly half the price of what racers might be spending on their Formula Fords, these types of cars seem relatively affordable.

The main rivals to the Wests in the Prototype Series are the Radicals, which do have their own series, though other manufacturers to have featured include Stohr, Spead, Minetti, Chiron, a new pair of Wolf GB08Cs and a Prince, which uses a Formula Ford as its base point. Laucke feels there is more to come from his West.

“I’m just starting to tap into its potential.”

After Auto Action’s latest Under the Skin feature? Pick up the latest copy of magazine, in stores every second Thursday. Also follow us on social media Facebook, Twitter and Instagram for all the latest news.