UNDER THE SKIN: NISSAN R88C

GO GO NISSAN!

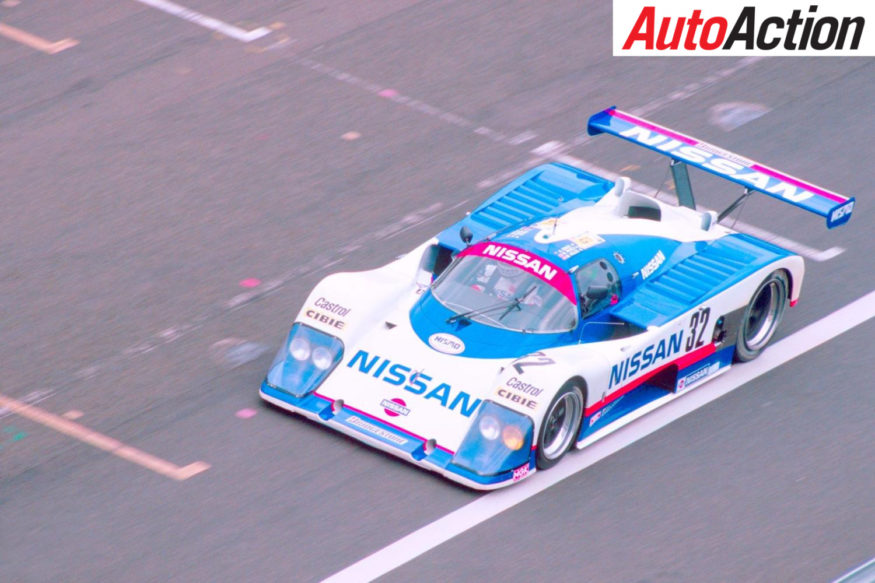

Nissan has had a long – and somewhat chequered – history in sportscar racing. But one of its most fascinating Group C racers, the R88C, now resides in Australia, and represents a snapshot of the company’s racing heritage

By Phil Branagan

WRITING ABOUT a racing car should be relatively straightforward.

Here is what it looks like, this is why it looks like that, what do you think?

But to understand the Nissan R88C, it takes more than that. Yes, it’s a classic Group C car from the 1980s – but it is not one of the eras most successful. And yes, it is a thing of, if not beauty, then possibly… elegant brutality?

And we will be honest here; there is a big Australian connection with this particular car. The head of the company’s UK-based racing programs at the time was Howard Marsden who, if he was not born here, is the kind of Pom we would like to have a few more of here. Alan Heaphy reported to him, and ran the team’s hardware. And now, the car lives down under, having made its public debut at the World Time Attack at Sydney Motorsport Park last month.

So time for a confession. We do not have a lot of images of the car’s insides. As pointed out in this feature by no less than Allan Grice, getting the engine cover off the car is a pain; getting its nose off is even harder and, in terms of doing it during a race, practically impossible.

So it is something of a challenge to look under the car’s skin. But the story of the car is not a bad one…

Thirty years ago Nissan had two international sportscar programs; one in the UK, based in Milton Keynes, and one in the USA, based at El Segundo, near Los Angeles. Differing rules between the two series meant that the cars that ran in either series shared some parts, but were far from identical, and grew ever less so with each passing season. In 1985, both programs developed Lola-based cars, powered by a Nissan V6 engine. The American regulations stated that the cars had to have a production-based motor so that is what both programs ran. In the USA, the units retained the original cast iron block, just like the road car. In Europe, that was changed to aluminium, without great success, no matter how hard the team worked for the following year.

So there were changes for 1987. A bespoke V8, the VEJ30, was developed, and fitted into a chassis designed and built by March. Despite the new engine, it also proved to be unsuccessful.

“They built three or four chassis for the 87G, it had the V6 engine in it, which was production based,” says Heaphy.

“It was all headed up by Dr Yoshimasa Hayashi, who was a lovely bloke.”

He may have been. But that engine was not a success so, for the following season, they did it again, with the VRH30. Such were the tight timelines in developing a fresh powerplant that Dr Hayashi and his men had eight months to get it right. The first engine was fired up at the end of 1987 – in fact, on December 25…

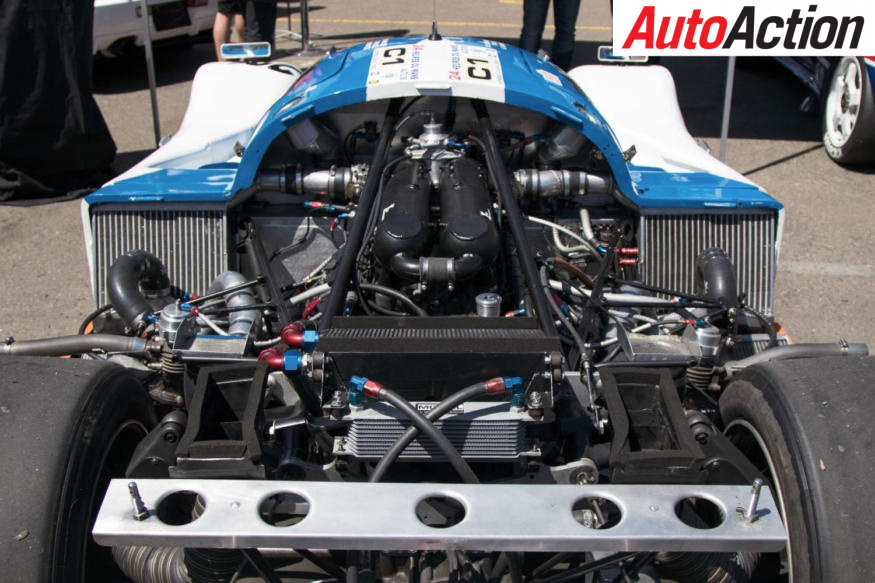

“The ’88 car had the first of the V8s engines, quad cam, quad valve – basically a bigger version of the Cosworth DFV, but bigger and with turbochargers it,” Heaphy remembers.

“In ’89, the engine was 500cc bigger, but it was a much smaller unit, and with much more power. I am not going to say that this engine was not good but it was a bit of a challenge.”

One of the challenges was the fact that the chassis from the 87G was carried over, but the wheelbase was lengthened (by 65mm) to make room for the longer engine, and to improve the aerodynamics. In itself that proved to be difficult; some of the aero was done in the UK, in a ¾ scale rolling road windtunnel, and some of it was done in Japan.

The engine was much different. It had the same V-angle and 66mm stroke as its predecessor, but the oil pump was mounted outside the engine block (rather than internally), and the IHI turbochargers were fed by bigger oil galleries. Each engine cylinder bank had its own plenum chamber, which allowed two 3.6-litre chambers to replace one of 7-litres on the VEJ30.

The engine, for which 28 blocks were cast, ran in several different specifications and states of tune, as Le Mans demanded reliability, above all else. The Nikasil cylinder liners and the usually steel cam bearings were both replaced by sturdy cast iron items for the 24 Hour, where the usual 9000rpm limit was dropped to 7500rpm. The drivers of the #23 car were allowed 9600rpm for Qualifying and with 2.8 bar of boost, they had around 950hp to play with. In the race, with 2.4 bar, the engine was rated at “over 750hp”.

The team focused on running its older cars in several lead-up events, without success, and when the car proved to be well off the pace of the leading Jaguars and Porsches, the signs were not good. Changes needed to be made, and they were. The March-built chassis were the last of the aluminium tubs, with most of the opposition now adopting carbon fibre chassis, which is what Nissan itself did for 1989. For that technology Nissan turned back to Lola.

Le Mans was not a success for the R88C. Two cars went into the race and only one finished, the Allan Grice/Win Percy/Mike Wilds car. It was 50 laps down, after having a gearbox replaced. The other car, for Kazuyoshi Hoshino/Takao Wada/Aguri Suzuki, had an engine failure after 286 laps.

This is the car that now lives in Australia.

The UK cars were not proving to be successful – and that was put into even sharper focus by the fact that the US program was going very well. New recruit Geoff Brabham had delivered the Nissan its first win in Miami in 1987, and when team switched to Goodyear tyres for ’88, the winning streak got longer and longer. That car was now largely designed and developed in-house by Electromotive Engineering and against similar opposition to that faced on The Continent – Porsche 962s and Jaguar V12 – the Nissan team was becoming a force on that side of the Atlantic.

After the race, in the Japanese championship, one of the R88Cs managed to score back-to-back podium finishes, but it was obvious that Nissan needed a fresh start for the 1989 season. It made one; Lola was again engaged to build the cars’ chassis and perform the aero development, in partnership with their Nissan UK partners.

“Some of that came out of Europe, it would have to,” says Heaphy. “With the ’89 and ’90 car, we spent a lot of time in a three-quarter scale tunnel near Bedford, we did a bit of that.”

There was also another, all-new motor and this time, Nissan got it right.

“The second [V8] was 30kg lighter, it was chalk and cheese,” says Heaphy. “It mounted lower because it was so much smaller. It was all developed in-house.”

The engine was made at Nissan’s factory in Oppama, which is also the home of the NISMO Engineering Center, and was much more powerful than the VRH30. But it was still not perfect, and that car led to one of the more interesting anecdotes about the Nissan program.

“They were very conservative,” says Heaphy of his Japanese counterparts.

“We could never get the fuel consumption right. It was a fuel consumption category, and on the last lap – I don’t know how many times – the fuel pressure would drop on the last lap. It was a fuel guzzler, I don’t know how they got the car through the 24 Hours.

“We had a little genius working for us, Steve Wills. He was a motor racing nut, 20 years old, maybe 21, he loved racing, and he used to install X-ray machines. Very cluey, but he wanted to work in motorsport. The engine ECU was supplied by JECs, sealed. He said that he could break into it…

“In 1989 I spoke to Weslake, they had a very good dyno facility, and we set up an engine on their dyno. We broke into the software to re-tune it, and we got a podium at the next race [Ed: Mark

Blundell/Julian Bailey finished a season-best third at Donington Park]. They took it very badly; Howard did not tell them what we had done until afterwards. We kept retuning it, but then the racing program ended.”

Not before there was another generation of car, the R90C, but the rules of Sportscar racing were evolving. Manufacturers were now being asked to commit to a whole season of racing to qualify for a Le Mans invitation, so the funding required was growing. In the USA, the Electromotive program had proven to be wildly successful, with Brabham winning consecutive titles before Nissan bought out the program in 1990. He kept winning and Nissan set its sights on bigger fish, namely the Champ Car Series.

Sportscar technology was also changing. The FIA announced a new formula for 3.5-litre, normally-aspirated engines, which mirrored the technology in Formula 1.

“In 1991, the normally-aspirated era was starting, they even made a big investment in Electromotive in the USA, to design and build a car for that.

“It was a V12,” says Heaphy, “there were three or four engines built, one car completed and two others in bits and pieces.”

By mid-1992 their an engine was ready. It was track tested, but looked to be down on power compared to the opposition, led by Jaguar, Mercedes and Peugeot.

But the real problem was a downturn in the Japanese economy. Money needed to be saved, and Nissan scrapped its sportscar programs, to concentrate on production-based competition.

Nissan has returned to the top tier of sportscars, now known as LMP1, without success, and has now departed again – but its form in LMP2 has been very impressive. The R88C might be something of an orphan; only four cars were made, and one of them resides in Nissan’s Heritage Collection, an extraordinary, by-appointment-only museum tucked into a corner of its Zama factory in Kanagawa Prefecture.

The R88C may not have been the success that Nissan wanted it to be. But it does stand as a symbol of the company’s commitment to motorsport. Having one of the cars reside here in Australia – where so much of Nissan’s racing DNA was displayed – just makes it that little bit more special…

Behind The Wheel

ONE MAN with experience in the R88C was none other than Allan Grice.

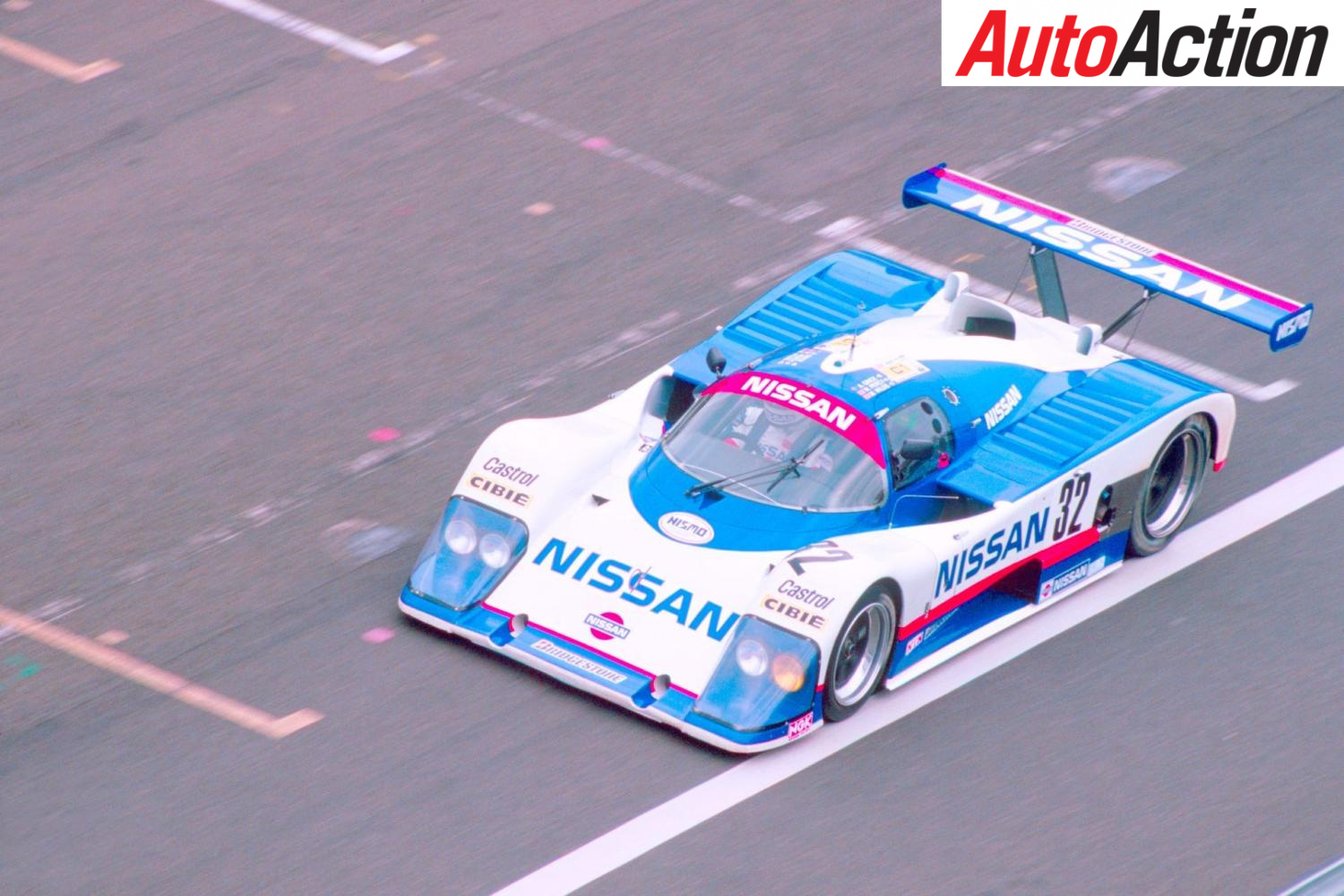

As a part of Nissan’s driving squad in the 1980s the Bathurst legend joined Win Percy and fellow Brit Mike Wilds in the #32 entry for the Le Mans 24 Hour race, and

Grice enjoyed driving the car – even if it did not go the distance.

“I had driven a Group C car, a Porsche 956, at Le Mans before that,” he told AA, “so I was ready to deal with the fact that the car would go into a corner faster than your brain would. The springs were so hard it would go over the kerbs like a badly-behaved billy kart.

“The Mulsanne Kink was a 190mph corner in those days, and it was flat, easily. On the other hand, you would bounce the car off the road in the chicanes!

“It was there, on the money, but it was not as good as the Porsche at the time. They had made a profession out of running the long-distance races, whereas companies like Toyota and Nissan would go there, try hard, and then go away for a couple of years. That does not work as well.”

Grice also realised that while a great deal of work had gone into the car’s engineering, some of the items on the car were clearly less of a priority than others.

“Everything was designed by committee,” he says.

“I remember going there to test one time, and they had had some unreliability with the turbos. You had to pull the back of the car off to get at the turbo, which turned a 10-minute stop into a two-hour stop! That was a good idea…

“We cut down on boost and revs, which made it a bit of a reliability trial, but the most important thing to the Japanese was to finish the race. We qualified quicker than the Japanese car, and when I jumped in the car for the first stint, I got on the phone to Howard. ‘Howard, this thing either has no boost or they have changed the final drive ratio!’ ‘Righto Allan, I will go and see Kakimoto’. About 15 hours later, they had to change the gearbox, they woke me up and I jumped back in the car.

“First time down the Mulsanne, I told Howard, ‘Changing the gearbox seems to have fixed the turbo!’ They had the right ratio in the spare gearbox.

“It was a good car to drive, nothing dangerous or nasty, with good power. We never ran anything like the boost of the ‘Japanese’ car – I would like to have driven one lap, just one lap, with the boost up. But, it did the job.”

THE FACTS

NISSAN R88C

Overall length: 4780mm

Width: 1990mm

Height: 965mm

Wheelbase: 2800mm

Track: F 1600mm/R 1550mm

Engine

Nissan VRH30T DOHC, 4 Valves/cylinder (32 valves)

Configuration: 90-degree V8

Aluminium-alloy block and head

Forged steel crankshaft with five main bearings

Twin IHI turbochargers with multipoint electronic fuel injection

Capacity: 2996cc (85mm x 66mm)

Compression Ratio: 8.5:1

Power: ‘Over 750ps’/551kW @8000 rpm

Torque: 542lb-ft (735nM) @5500rpm

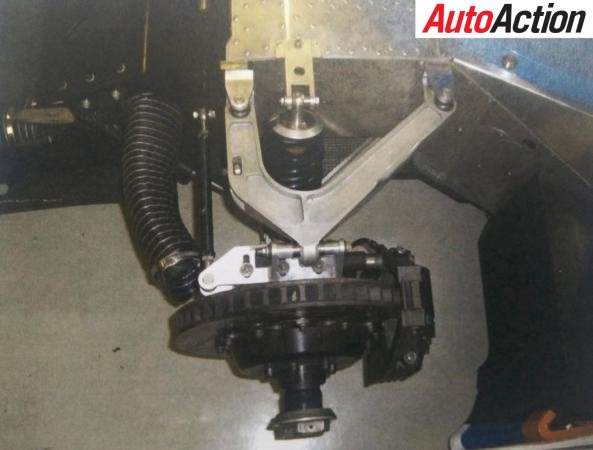

Transmission: March 87T, five-speed manual gearbox

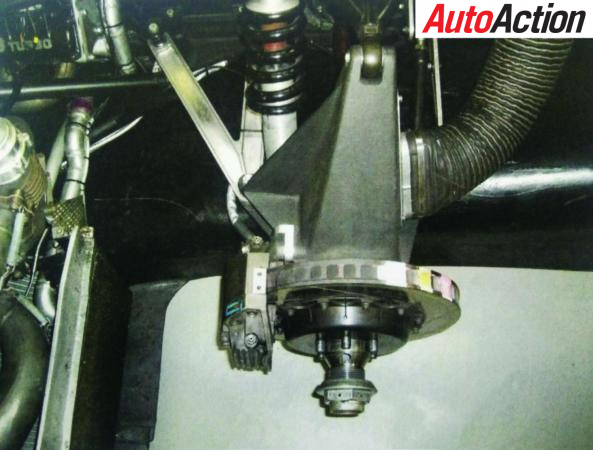

Suspension (F/R) double wishbones, coil springs over dampers, anti-roll bar

Brakes: Ventilated rotors 356mm diameter with four-piston AP callipers F & R