James Garner’s Grand Prix

By Jason Crowe

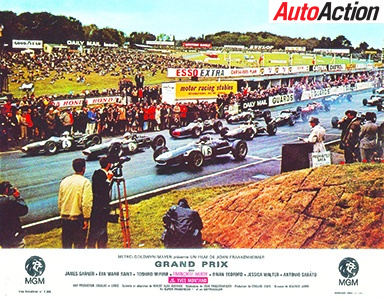

John Frankenheimer’s 1966 film Grand Prix is a favourite among race fans for its attention to detail and authentic trackside atmosphere. The film would also ignite a lifelong passion for its lead actor.

THE 1966 Grand Prix season was as exciting as it was historic. Jack Brabham won four races and would go on to win the last of his three championships, cementing his place as one of the greats in the sport.

What is less known than Brabham’s monumental achievement is that in the background another grand production of its own was taking place. Hollywood director John Frankenheimer and his crew shadowed the teams throughout Europe for much of the season making a movie that, they hoped, would do the season justice.

Frankenheimer was determined to give moviegoers a realistic racing experience. He was confident that he could pull off the enormous project and deliver a film that would be believable, from both professional drivers and race fans’ perspective. He succeeded; even 50 years later Grand Prix is still considered by many to be the sport’s best movie.

For this undertaking Frankenheimer assembled a small army of actors, technicians and the world’s leading racing drivers. He also pioneered movie making and camera operating techniques that would be the new benchmark in the industry. Realism was an important ingredient for Frankenheimer; he was adamant that actual footage from F1 races was to be used to give filmgoers an authentic F1 race atmosphere.

A deal was struck by the films producers that would see Bruce McLaren’s newly formed McLaren team present their new car, the McLaren M2B, in identical livery as the fictional Yamura car to be driven by Garner.

Key race scenes were to be filmed by Phil Hill and Bob Bondurant who drove specially modified cars during practice sessions during the Monaco and Belgian Grand Prixs.

The next hurdle for Frankenheimer in his quest for realism was training the lead actors to drive at high speed. That took planning.

James Garner, Yves Montand, Brian Bedford and Antonio Sabato Jr were the actors chosen and, if the film was to achieve the level of realism Frankenheimer wanted, they would need to act their part in the actual cars, at high speed. Garner was a noted car enthusiast; the others were less so. In fact Bedford didn’t even have a drivers licence before filming started…

Enter Bob Bondurant. The American had gone from a grassroots racer who had successfully raced Corvettes and Shelby Cobras to a man racing a privately owned BRM in the 1966 F1 Season. At the request of Frankenheimer and Carroll Shelby, Bondurant met the four actors at Riverside Raceway outside of Los Angeles, where each was given a ‘hot lap’ to see which of them could stand up to the white knuckle speeds and which one of them would be more suited to the lead driver role.

Bondurant recalls that after “scaring the shit” out of the first three actors Garner was laughing like an excited child, at speeds of over 240kmh, with Bondurant at the wheel.

“This is your man,” said Bondurant when he pulled into the pitlane.

Shelby, who took the mantle of ‘Technical Advisor’ for the film’s racing scenes, assigned Bondurant to be Garner’s personal instructor.

Over the next week, Garner underwent a driving course at Willow Springs Raceway, using a Shelby Mustang GT350, small open-wheelers and finally, Formula 1 car.

The result was that, in a relatively short time Garner turned into a driver capable of holding his own, even against professionals. Frankenheimer had a surprise ace up his sleeve and went on to use Garner in as many racing shots as he could.

Not only was Bondurant competing in the 1966 season, he was also the actors’ racing coach and one of the main stunt drivers in the film. Phil Hill was to assist Bondurant in the real race scenes, along with cameraman Jon Stevens.

In 2016 parlance, can you image Lewis Hamilton and Jenson Button filling those roles and doing the same today?

Although Bondurant said that Garner was ‘light years’ ahead of the other actors as far as being a competent race driver, he also heaped praise on Garner’s co-star, Yves Montand saying that he was a “fast learner”.

With the actors now behaving and driving like real GP racers, thanks to Bondurant, Frankenheimer could now be confident in filming the races.

To give you an idea of the realism Frankenheimer was hoping to achieve at the Monaco GP he staged a mock start less than an hour before the actual race! There were 16 film cameras situated around the track, as well as the Super Panavision 65mm fixed to Phil Hill’s car. It is said that the crowd was more enthusiastic about the mock start than they were with the actual race.

Post-race while Jackie Stewart was receiving the real winner’s trophy surrounded by adoring fans, Frankenheimer staged the mock winners presentation, in which Montand received his trophy using the same crowd.

The Belgian GP shoot saw Frankenheimer arrive a week before the race with his army of experts that included Graham Hill, Jack Brabham, Jochen Rindt, Richie Ginther, Jo Bonnier and Bondurant. The A-List drivers drove the circuit in racecars and camera cars all owned by MGM. Such was the level of co operation the producers were getting, the Belgian Automobile Club allowed Phil Hill to drive a film car around the track, for one lap, in the actual race!

That was a bittersweet occurrence. Hill drove through a huge accident on the first lap that would see more than half the starting field out of the race, and Stewart taken to hospital. Hill’s footage is the only film of the accident.

Following the script, Garner’s character, Pete Aron – one letter different from ‘Amon’ and with a similar helmet design – won the race in his Japanese Yamura (think, Honda), which was painted in a scheme similar to the McLarens of the day. Talk about coming full circle…

Problem was, the race’s sole McLaren didn’t even start the race, thanks to a wheel bearing failure in Practice, so Frankenheimer had no vision of the Yamura in action. Bondurant’s BRM was painted white, literally overnight, to match Garner’s car, and the next day the director got the footage he needed to edit the car into the race.

As the season went on, there were other obstacles to overcome. Starting with the converted Formula 3 cars, supplied by and tended to by Russell, was one thing. Then they moved onto some of the 1.5-litre F1 cars that had been made obsolete by the FIA changing to the 3-litre engine regulations. Garner made the transition easily; Montand could drive the more powerful cars, but not nearly as fast as the American; and Sabato and Bedford needed more help than ever.

Production of the movie finished on-schedule and on-budget and ‘Grand Prix’ opened in December 1966 to strong reviews. It was nominated for three Academy Awards and won all three; Stu Linder for his brilliant editing of the race sequences; Frank Milton for Sound Mixing; and Gordon Daniel for Sound Editing. Although John Frankenheimer’s ground-breaking achievements were ignored by the Academy, he was nominated for Outstanding Directing by the Directors Guild Of America.

And we as race fans are thankful for his efforts.

Garner’s new-found passion for motor racing would last for years. He went on to race in the USA, and loved the sport for the rest of his life. He passed away in 2014; such was the standing of Grand Prix that his obituary was published in several motor racing magazines, including Autosport.

Car’s the star

The vehicles used in the making of Grand Prix almost rivalled the actual F1 circus itself. A reported 22 race cars that included four BRMs, three Lotuses, four McLarens, four Ferraris, two Brabhams and two American Eagles were used in filming. These cars were either purchased by MGM, hired or even loaned.

To keep such an extensive collection of race cars on the track a travelling machine shop was needed which included highly skilled mechanics and workshop technicians. Equipment carriers and car transporters were also needed to haul these cars and relevant equipment from race to race.

The two film cars are just as famous as the F1s they were to film.

Since Ford was Grand Prix’s official supplier of cars they provided MGM with a GT40 running a Le Mans bred 427 and a Shelby Cobra that also packed the 7.0 litre under its hood.

These cars were needed as they could keep pace with the 150mph speeds that the F1 cars were generating. By all reports they kept up with 3.0 litre F1s with ease and were reliable during the extended filming schedules. The GT40 was especially useful as the camera was able to be forward mounted due to the GT40s rear mounted 427.

Steve McQueen would use a similar GT40 setup in his later 1970 production of Le Mans.

While filming in Europe Ford sent Garner a black Shelby Mustang G.T. 350H for use in the film and for his own personal use while the film was being made.

Always the gentleman and having his wife and child with him on the set, Garner thought the car was attracting too much attention whenever he took it out. To solve his predicament Garner offered the car to an appreciative Bob Bondurant. Garner and Bondurant would become life-long friends.

Give the man an Oscar

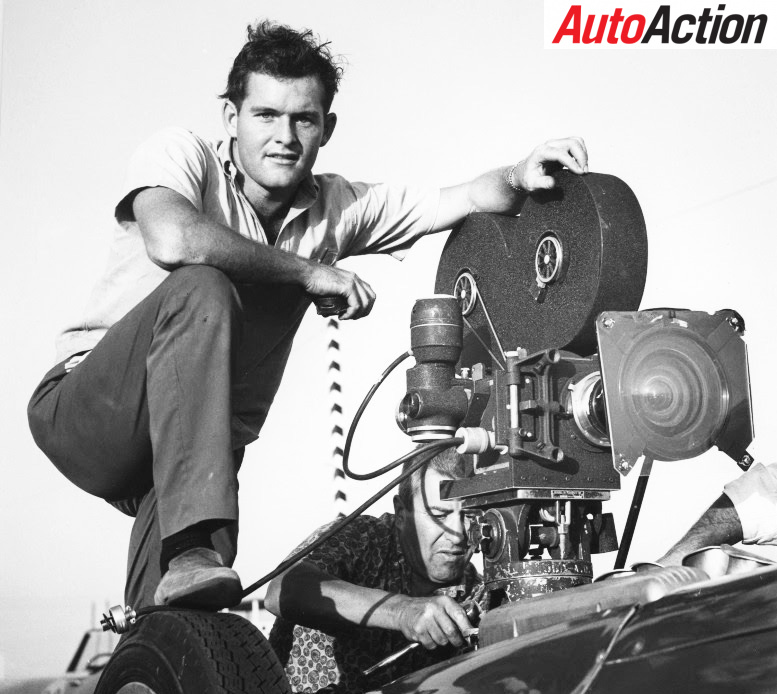

In 1966 there was no such thing as an in-car camera, certainly no GoPro. If you have ever seen a film camera from the 1960s you will know they are a huge and serious piece of kit.

The camerasFrankenheimer demanded were Panavision’s finest – the Super Panavision 70, a 65mm camera.

Frankenheimer lured John M. Stephens to the project with the promise of shooting sequences of racecars at over 300km/h from a specially modified race car. Stephen’s acceptance would see him literally redefine the industry of action filming.

Stephens invented a mechanism that allowed the Panavision cameras to be mounted to a F1 racer and be remotely controlled from a helicopter or camera car. The remote control system was adapted from missile testing telemetry technology. Stephens now had remote control and instant information of footage used, focus, panning and elevation of the car-mounted cameras. Stephens also acknowleged Frick Enterprises for designing the various camera mounts needed to support the weight of the large cameras.

The high-speed pan and scan scenes where the camera pans from actors James Garner to Brian Bedford (actually, Jackie Stewart) at close to 260km/h are, to this day, breathtaking to watch on the big screen.

Stephens also overcame two major problems with camera technology while filming at high speed. The G-forces (around 1.1) generated when cornering resulted in the 65mm film reel pressing against the cartridge. This friction caused constant jamming of the camera. To overcome this setback Panavision developed a purpose-built cartridge with an internal reel that rotated with the spool, thus eliminating camera jamming.

Another problem Stephens faced was the strong head winds. The drive belts in the cameras would distort, resulting in blurred footage. Panavision’s engineers solved this problem by building silent gear drives for the film cartridges.

It is somewhat disappointing, then, that Grand Prix did not win an Academy Award for its breakthroughs in movie making technology.