FALCON GT GLORY

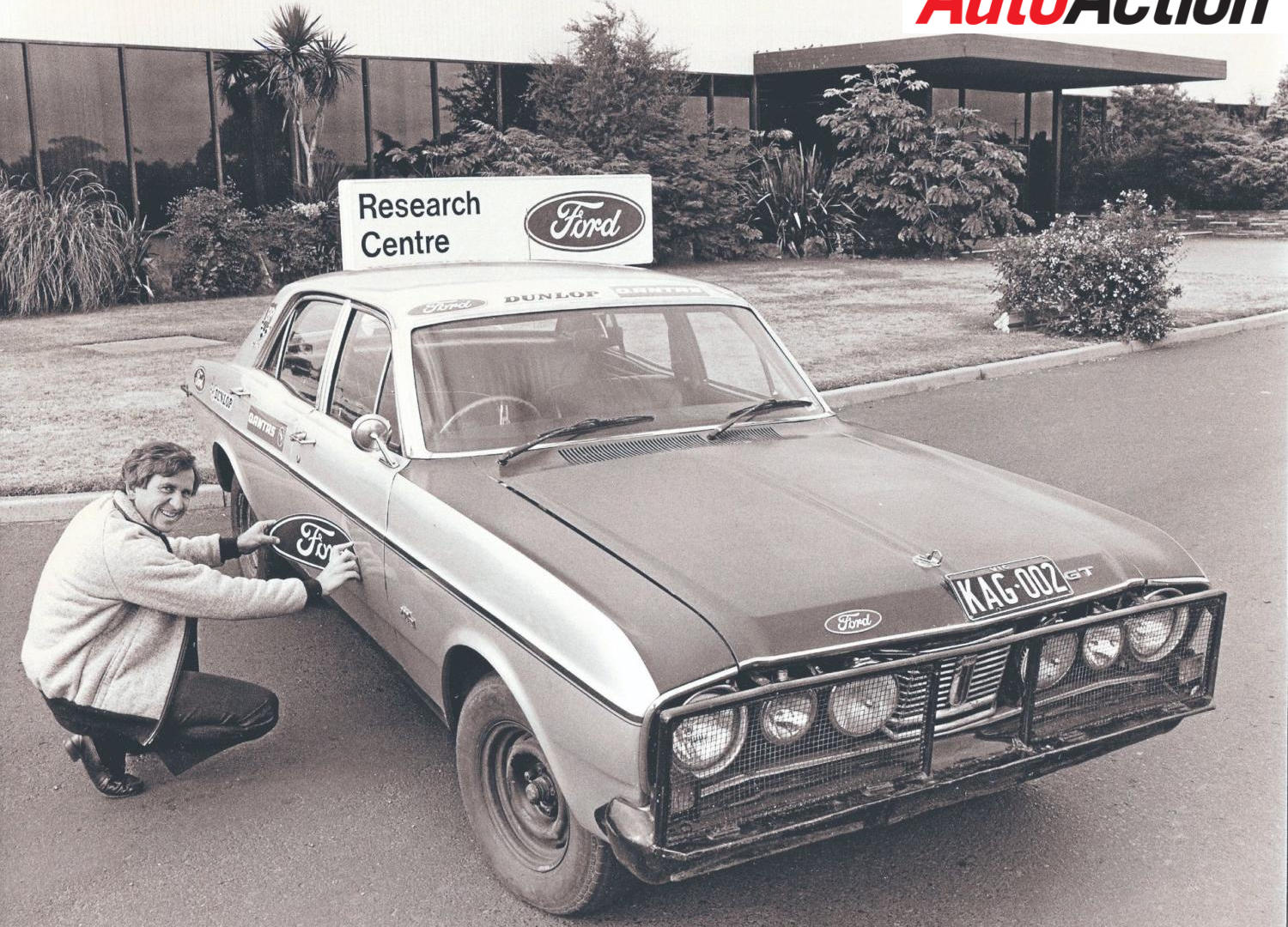

A young Ian Vaughan, applying the finishing touch to the newly-completed KAG 002 at Broadmeadows

The man who led the XT Falcon GT charge to the coveted teams’ trophy reveals how a bunch of Aussies beat the world in the greatest road race ever.

By MARK FOGARTY

Against the might of rival Ford outfits from Britain and Germany, full factory efforts from then UK giants Austin and Hillman, and heavily supported entries from Citroen, Porsche and Mercedes- Benz, it was the Blue Oval’s Australian squad that was the most successful team in the 1968 London To Sydney Marathon.

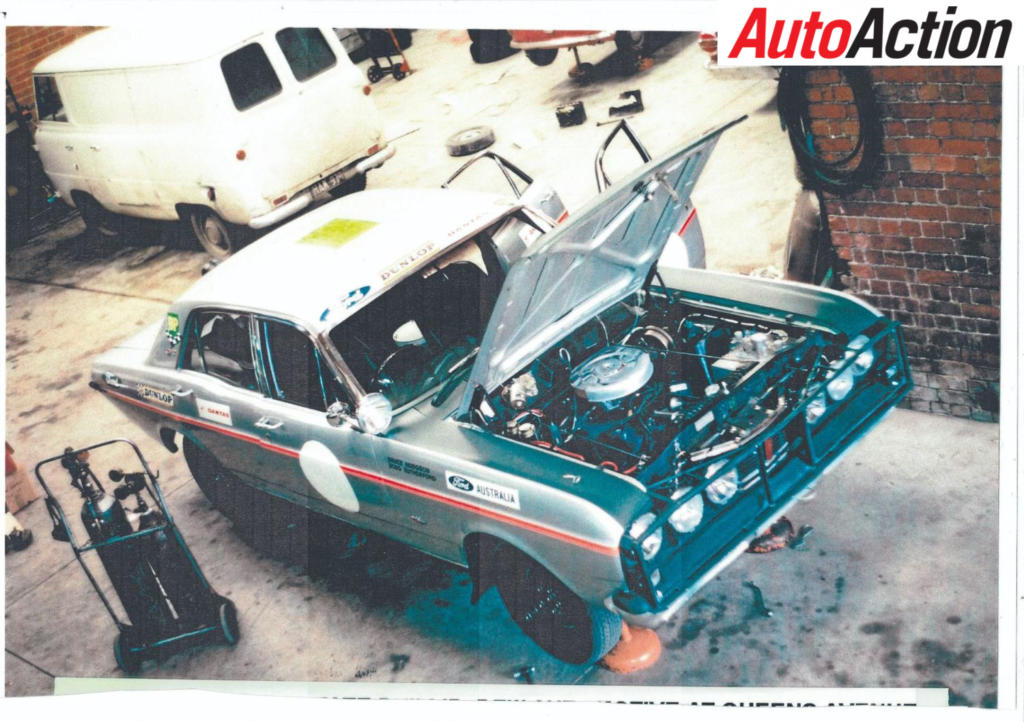

Leaving the London start in front of Westminster and Big Ben

Ford Australia’s three XT Falcon GTs all finished in the top 10, with then Broadmeadows engineer Ian Vaughan leading the way in a spectacular third place. The other big Aussie V8s came in sixth and eighth, clinching the teams’ prize against international opposition.

They outlasted the fast-but-fragile Ford UK and Ford Germany cars – as much rivals as corporate cousins – and beat the powerful Anglo- Australian British Motor Corporation armada of Austin 1800s.

The Roaring Fordies also trounced the unofficial – but nevertheless heavily factory-backed – Holden Monaro team, gaining sweet revenge for the XT GT’s Bathurst 500 defeat.

It was a truly world-beating achievement that added to the Falcon’s growing lustre under Broadmeadows’ American boss Bill Bourke, who used performance and racing to enhance the homegrown Ford’s image.

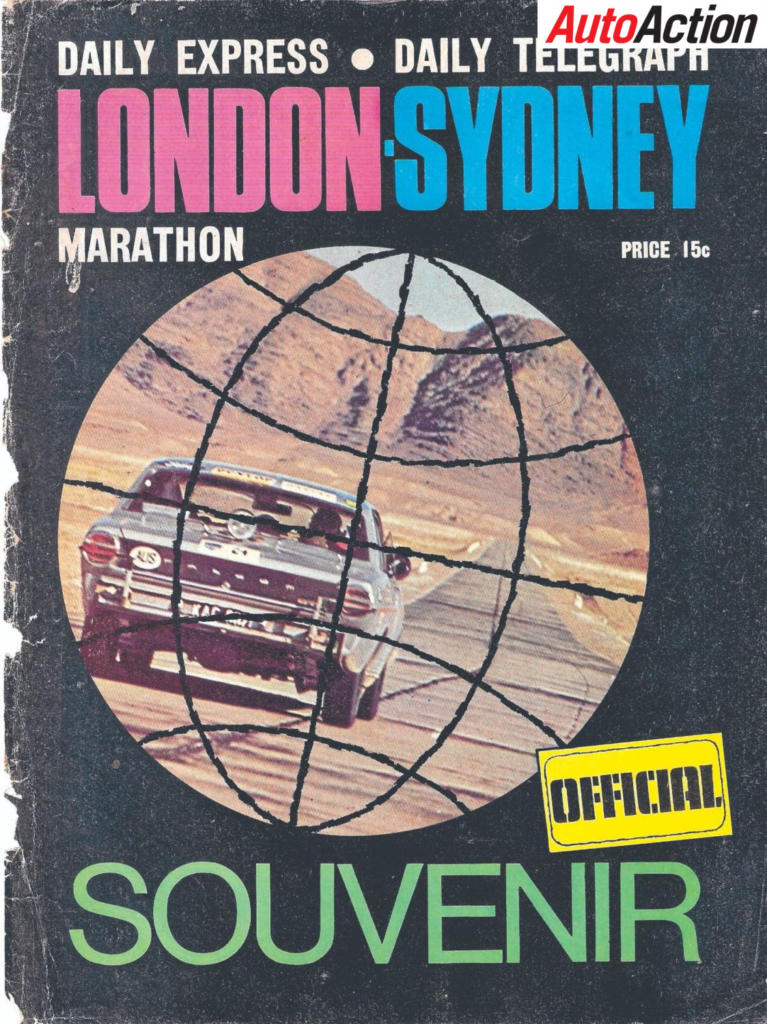

This month is the 50th anniversary of the finish of the greatest cross- continents motoring event ever staged. In fact, the first – and most famous – London To Sydney Marathon was a road race across Europe, Asia and Australia, run relentlessly for nearly 17,000 km. It was also a torture test for men and machines, especially on the largely outback tracks of the final leg across Australia.

French ace Lucien Bianchi had it shot to pieces in his Citroen DS21 until eliminated in a bizarre crash in the closing stages. That dramatic misfortune handed the win to taciturn Scot Andrew Cowan in a Hillman Hunter, ahead of charismatic Irish race and rally star Paddy Hopkirk in an Austin 1800 ‘Landcrab’, followed by Vaughan’s now-famous KAG 002 XTGT.

It was an adventure for the ages and spearheading Ford Australia’s teams’ victory did no harm to Vaughan’s career trajectory at Broadmeadows. An accomplished amateur rally driver in the 1960s, he rose to No.2 in the company as vice- president of engineering and design until he retired 15 years ago.

Vaughan, now a sprightly 76, was the ‘father’ of the Falcon-based Territory, Ford Australia’s trend-anticipating SUV that was a top-seller until local production ceased in 2016.

He co-drove what was nominally the Ford Motor Company of Australia’s second entry in the London To Sydney, co-driven by rally buddies Bob Forsyth and Jack Ellis. Official team leader was Ford Oz competitions boss and still gun race and rally driver Harry Firth, who took accomplished rallyists Graham Hoinville and Gary Chapman along as essentially ballast.

The third GT was crewed by Australian rally star Bruce Hodgson and co-driver Doug Rutherford, gambling on surviving one man down to save weight and gain performance.

Although fastest to Bombay (now Mumbai), Firth later took a mechanical risk that cost him a podium place or even the win. He was the last of the Falcons home in eighth, with Hodgson – later of GTHO Phase IV prototype ARC fame – finishing a crucial sixth.

The team, much to the famously autocratic Firth’s chagrin, was run by young Broadmeadows PR executive John Gowland, a club motor sport enthusiast who was appointed team manager.

According to Vaughan, the audacious entry against star-studded European Ford teams – led by British rally star Roger Clark – was a result of the ‘Mustang-bred’ broom that had swept through Broadmeadows under Bourke.

“Rallying was important for advertising in those days. We used to rally on Sunday and advertise on Monday,” Vaughan recalls. “Bill Bourke decided that we should add rallying to racing with the GT and really get the story right. Ford Australia had relaunched itself with the XR/XT Falcon, so it was a good way to reinforce that. So it was decided that we would run three cars and John Gowland was appointed as the team manager, and we selected our drivers out of the Ford factory rally team, which had been doing the major Victorian and Australian rally championship events.

“It was different to the Holden team, which GM didn’t get behind officially. It was a bunch of people driving the Monaros that weren’t co-ordinated by Holden. There was a lot of back-room stuff going on, but it wasn’t an official GM entry. Fortunately, Ford Australia did run an official works team.

“It was an exciting time, with the ‘Going Ford Is The Going Thing’ slogan and all that. It was a very upbeat time. The Marathon was projected as an absolute adventure across the world. It was a navigation event, it was a driving event, it was rough roads, and we thought the Falcon would handle the rough roads well.

“We knew we wouldn’t be as fast as a Lotus Cortina, particularly with Roger Clark at the wheel. Clark was going to drive like a demon and if the car held up, he was going to be first there. But as it turned out, the Lotus Cortina couldn’t handle that sort of pace and we were conscious that we were stronger and more durable than the others, although it was a big car and if you went off the road, you were in big trouble.”

Ian Vaughan

Vaughan admits in hindsight that he could have pushed harder, earlier, and possibly challenged for the win.

“We probably drove a bit cautiously,” he said. “I certainly drove too cautiously in Asia. Guys like Roger Clark and Rauno Aaltonen were going flat, flat chat all the time. They were seasoned rally racers out of Europe, whereas we were coming out of what were largely navigational trials on dirt roads in mud and slush.

“We were trials drivers rather than rally drivers and it showed in the speed that we were driving at. We were driving at 95 per cent of what those guys were doing. Roger Clark drove at 100 per cent the whole time. But it caught up with him because the car couldn’t handle it.

“We were really competing on a different plane, but in a way, it helped us because so many cars broke down because they were being over-driven. We under-drove our cars. I think it also helped that I was an engineer. I drove the car with a sensitivity to its strength and a reserve because I’m a conservative engineer.

“I was hanging back so the car would last. I was never going to be the quickest and we were 11th when we got to Bombay. It was further back than I wanted to be – I thought around about seventh would be good – but I knew how rough the Australian leg would be and that there’d be some casualties there.

“From Perth, we moved up pretty quickly. We felt pretty good on our home turf and I started to pick up positions as we went across Australia. The other area where we did really well was in the Alps in Victoria and NSW. I did feel I was on my home turf there – I knew so many of the roads. We felt confident in Australia, whereas we were a bit tentative in Asia.

“It was a long event – nearly 17,000 km – and I’d never driven an event that long before, so I didn’t know how much I had to save the car. I probably saved it too much in Asia, but when I got to Australia, I felt that we could really give the car what it can handle.”

Vaughan remembers that winning the teams’ trophy rather than individual glory was the main goal. “We were hoping to win outright, but we were determined to win the teams’ prize,” he said. “We figured that would give Ford Australia the advertising value they needed – the Australian team that beat the world. We had to get to Bombay in good shape as a team to mount our real challenge across Australia.

“We were driving to finish as a team rather than driving to win.”

Vaughan, who British bookmakers had at outsider odds of 100 to 1 compared with Firth at a still 33-1 long-shot, bet on himself to finish in the top three.

“I won more money with a bet than I got in prizemoney,” he smiles.

Vaughan and some of his surviving teammates were reunited with KAG 002 – its Victorian road registration – at a London to Sydney Marathon celebration in Sydney earlier this month.

He drove it in a 25th anniversary re-run of the event in 1993, finishing second to Francis Tuthill’s Porsche 911, and was last behind wheel in

a revival version of the BP Rally in Victoria, which was a big event in the 1960s and ’70s.

Article originally published in Issue 1751 of Auto Action. Read the rest of the five-page feature here.

For Auto Action’s most recent features, pick up the latest issue of the magazine, on sale now. Also make sure you follow us on social media Facebook, Twitter, Instagram or our weekly email newsletter for all the latest updates between issues.