Peter Brock. The Icon

Over the years many of those people have spoken about the man, the racer and some of the things that happened, in public and behind the scenes. Many of those stories have been told, some over and over again.

So, on the 10th anniversary of Brock’s passing, AA wanted to speak to some of the people who worked with him but whose stories, perhaps, have remained relatively quiet.

Two of those people are Paul Weissell and Gerald McDornan. Weissell – ‘Wally’ to most people in the business – worked with Brock at Advantage Racing and the Holden Racing Team for 11 years, before exiting the racing game for a quieter life. McDornan was a part of the Pemberton Publicity team that worked alongside Brock since the 1970s and was, 10 years ago, working with Tim ‘Plastic’ Pemberton and Aaron Noonan on Holden’s Motorsport programs. Today, McDornan is still in the business as the principal of Veracity Media.

They both remember that September day 10 years ago.

“It started when I got the phone call from you [AA editor Phil Branagan],” says McDornan.

“I was working from home that day, and when I got the call, I rang the office and Plastic was not there. You asked if Brock was in Western Australia, so I looked it up, and you said, ‘There has been an accident’. I remember that call vividly.

“Noonan was holding the fort, so I said, ‘This is what I have heard, if anyone rings, you do not know anything’. By the time I walked to the car I had Mark Skaife on the phone.

“As I was parking in front of the office I heard Neil Mitchell on [radio] 3AW and he said, ‘We have heard from Perth that Peter Brock has been hurt in a crash’. From there on, it exploded. The rest of the day – and we left on that Friday about 9:45pm, helping the media with bios and so on – you could not count the number of phone calls we had.

“As I was parking in front of the office I heard Neil Mitchell on [radio] 3AW and he said, ‘We have heard from Perth that Peter Brock has been hurt in a crash’. From there on, it exploded. The rest of the day – and we left on that Friday about 9:45pm, helping the media with bios and so on – you could not count the number of phone calls we had.

“I went to Perth the next morning. That was the beginning of the most intense eight weeks that I ever worked, and we didn’t have even five minutes to reflect on how we felt about losing a mate – and to quite a few of us, a hero.”

It was much different for Weissell.

“I had been out of the industry for a while,” he says, “and my wife and I had a small business in fruit and veg, and we were working away at that and not really aware of what was going on in the motor racing world.

“All of a sudden my mobile phone went off. I have had the same phone number since 1990 so anyone who had rung the number, ever, rang it! I got phone calls like, ‘this is ABC Radio here, and are you aware that Peter Brock is dead?’ Before I had a chance to process the whole thing, you are trying to make a comment on live radio on the life and times of Peter Brock – and try to find out more about what was going on. It was a difficult afternoon to be taking phone calls from people.

“Later in the afternoon I was talking to ‘Hog’, Jeff Grech, and John Crennan, and we were hardly saying anything. We all found it very difficult to believe.”

One of the difficult things for people in the business to deal with was separating what they had to do in their professional lives and dealing with their own sense of loss – which was difficult to do.

“I grew up watching him win Bathurst,” says McDornan.

“He was one of my heroes, and they say that you should never meet your heroes. He was a great guy, a ripper to work with.

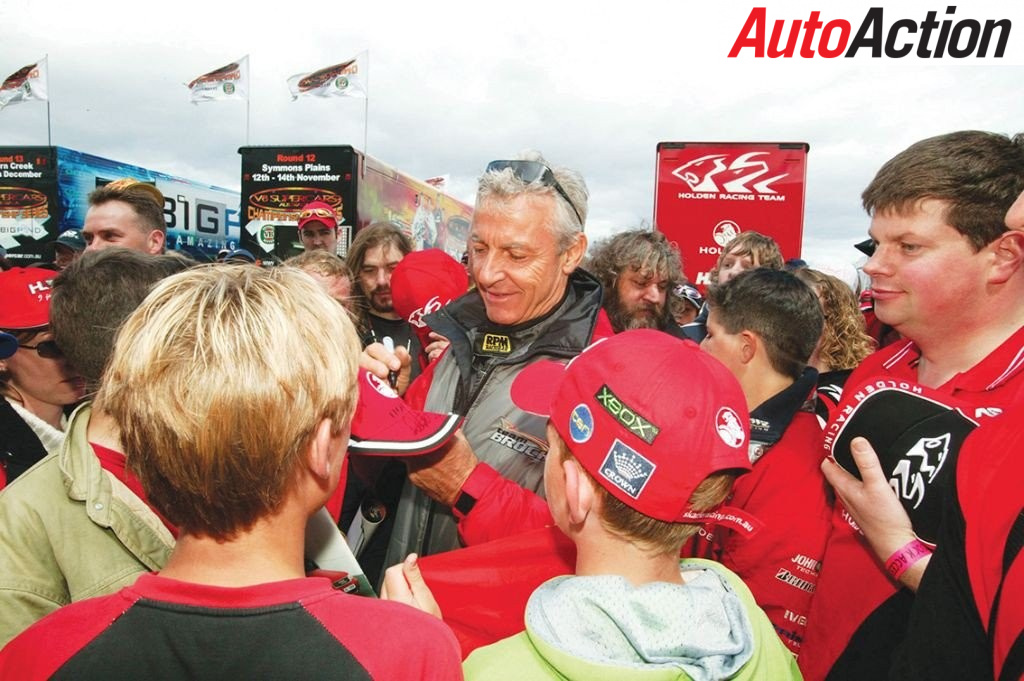

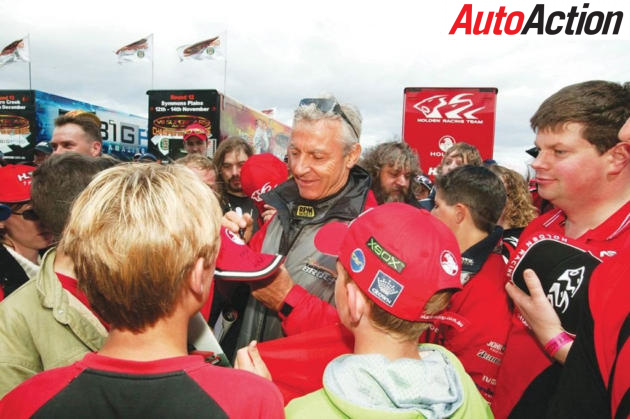

“On the Australian Safari, in the middle of nowhere, there would be a queue of people lined up to get Brock’s autograph. In one night, an hour outside Broken Hill, six people brought their kids up to meet Peter – and their kid’s name was Brock. In White Cliffs, where the buildings are underground, the queue was 100 metres.

That is when you stand back and think, ‘This bloke is a lot of people’s heroes’.

“That was the great thing about him; when he was in the office, once a month we might go out and have a bite to eat. Never had a wallet on him but he never needed one, because people gave him everything on the house. When you walked down the street, you would hear people saying, ‘That’s Peter Brock! That’s Peter Brock!’ The whisper was constant.

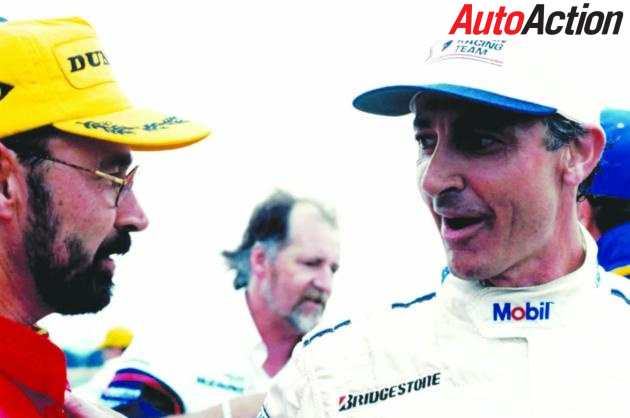

“To work with him, alongside him, at the IndyCar race [on TV coverage] in 1992 or ’93, was a thrill. I clearly remember about the night of the incident… whenever he was in the office he would sit there signing a pile of hats. A week before he went to the UK he signed a few, and there was one left. I saw it there and just before I walked out, I grabbed it. I never keep a lot of stuff but I have kept that.”

Weissell backs up the statement.

“The measure of the guy was, despite the pressure and the itineraries, he did not want to let people down,” he says.

“I would say, ‘Brock, you are supposed to be having lunch!’ – or whatever it was. ‘Oh yeah, but…’ There is a famous video of people pointing at that arsehole Wally because I was the one pulling him away from signing autographs. I didn’t mind being the one who looked back because he couldn’t look bad, or Plastic was looking bad! That is what we were there for.

“You appreciate what he did for the fans – and we really appreciated the fans – but you also annoyed that people could not separate themselves from that.

“The number of times you heard, ‘You will never guess what I called my baby!’ And I would say, ‘I know what you called your baby, you called your baby ‘Brock’, because he is your hero’. But people could not separate that hero from the racing driver, because you could not say to them, ‘Now is not the time’. If they could have been on the grid five seconds before the flag dropped, to get an autograph, they would have! And he would have signed it!”

A few weeks later, the media was still talking about Brock but in motor racing land, there was the small matter of the Bathurst 1000 – and the inaugural winners of the Peter Brock Trophy – to decide.

“At Bathurst… as much I was did not want to see a Ford win at Bathurst, there was never a more appropriate victory in that race,” says McDornan.

“Personally and professionally, I remember it like it was yesterday. It was a time that was so sad, but you were also so proud to do something that helped the family and helped his mates, and to contribute to his legacy. That is what he deserved for touching so many people. It was an absolute honour to be able to contribute to having his story told in a positive way.”